From Our Far-flung Correspondents Series:

Bogotá’s Symphonic Celebration of Colombian Folklore

(Versión en español aquí)

With a history spanning over 50 years, the Orquesta Filarmónica de Bogotá has become an international benchmark for its extensive repertoire of Western, traditional Colombian, and Latin American music, as well as its symphonic fusion with genres like rock and salsa. The repertoire selected for each season is as versatile as the mastery of its performers in reproducing the authentic sound of each era and region.

It was a delight to revisit the living photograph of what was the first venue I attended to listen to the OFB, the León de Greiff Auditorium. This architectural work, in the heart of the Universidad Nacional de Colombia and declared a National Monument, has been the scene not only for artistic events but has also yielded its stages to vehement speeches of intellectual and social transformation. The recent renovation of the auditorium preserved the essence of its avant-garde design and its acoustic warmth, and the orchestra once again demonstrated its mastery of blending its frequencies with the wooden structure to obtain a wide palette of timbres. Another point that I must highlight is that the seating was not reformed with beverage holders as is happening in important international auditoriums. In my opinion, the combination of music and food is typical of restaurants.

Regardless of the generations of musicians, conductors, and arrangers who have made their careers in this orchestra, the diversity of its audience, and the interaction with new technologies, the hallmark sensory experience remains. On this occasion, the special program that was prepared to praise Colombia’s geographical privilege lifted an ecstatic audience that could not remain seated. This is another of the qualities in symphonic events that persist over time; it is not only Colombian or popular music that manages to motivate the listener’s interaction with the orchestra, the Bogotá public by tradition has always felt a great appreciation and admiration for Western musical expression. I recall on this same stage an intense silent conversation between Johannes Moser and the attendees, which culminated in a frenzy during the final chords of Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. 1 and the spectators’ cry of jubilation. As is customary in Colombia, the artists cannot leave the stage without parading through four rounds of applause and performing at least two pieces in the encore.

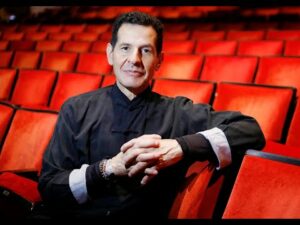

The June 15 concert was no exception; a full-house auditorium was gradually led on a cruise of emotions along the Pacific and Caribbean coasts of Colombia. In the interview that you will find below this article, maestro Rubián Zuluaga, assistant director of the Bogotá Philharmonic Orchestra, narrates how in this substantial selection of pieces a mixture of traditional rhythms with innovative orchestration techniques is manifested as if it were film music. The program is a compilation of instrumental and vocal works written for the traditional instruments of Colombian folklore, which have been adapted with great fidelity and creativity to symphonic orchestration. This is a task that the OFB has been pursuing practically since its foundation to preserve the country’s native cultural values. The collection of studio albums that has earned the orchestra two Latin Grammy Awards has been entirely dedicated to the recording of famous Colombian pieces.

The gala began with the work Canción de la Tierra composed by Andrés Sánchez Angarita, a double-bassist of the OFB. This piece, which is part of the album “Salvemos la Tierra Ya” by the same author, is an exaltation to biodiversity, but also a call to stop the uncontrolled exploitation of natural resources. The piece contrasts sections of great orchestral density with light melodies in the woodwinds, representing the immensity of the jungle and the mountains, and the fragility of the birds that fly over them. During the performance, overwhelming images of nature and the disasters caused by industry and excess waste were projected. Immediately, Pachito Eché by the Bogotá composer Alex Tobar, was the piece that raised the party atmosphere in the auditorium. It is interesting to see the evolution of this song thanks to its catchy melodies. Although it was originally composed in son paisa, an emblematic folk music genre from the Antioquia region, Benny Moré catapulted it to international success in a mambo version. This could be the reason why arranger Ricardo Hernández Mayorga has included a section in which the work moves to a 1950s Cuban dance hall.

In this fusion of Colombian rhythms with foreign music, it is worth mentioning the work of the composer Luis Eduardo Bermúdez who, thanks to his interaction with tropical music and jazz, gave a new meaning to the cumbia and porro genres. Lucho Bermúdez’s project resembled Benny Goodman’s Big Bands; traditional groups were transformed into large wind ensembles that played attractive harmonies and passionate improvisational solos. Colombia Tierra Querida, one of his most important compositions and which has become the country’s second anthem, is usually the closing work in such events. Although the performance was only instrumental on this occasion, it was inevitable that the audience would sing along to the refrain while accompanying themselves with their palms and swaying their hips to the spell of the cumbia. Likewise, each family of the orchestra performed their own choreography, and the percussion improvisation sections, essential in Caribbean music due to its African heritage, brought the gala to its climax. Transporting ourselves to the western region of the mountain range, where a deep ocean can be seen in which humpback whales find the waters warm for their mating season, the currulao brings together the flavors and knowledge of the Colombian Pacific. The Afro-Colombian composers Petronio Álvarez (1914) and Hugo Candelario (1967) have extolled the richness of this music so that it can be appreciated throughout the Colombian territory. From Bahía Solano to Tumaco, the chonta marimba is the emblematic instrument of Pacific folklore; the unique sound of its keys immediately transports us to this region. On this occasion, in what seemed to me to be a combination of the vibraphone and the marimba, the arrangements of Mi Buenaventura and Pacífico Amoroso translated the tonalities of this Colombian idiophone and recreated the freshness of the mangroves and coral reefs.

This festive gathering, in which the orchestra musicians wore colorful blouses and shirts, once again confirmed the importance of disseminating Colombian folklore through symphonic and contemporary language, preserving its identity and authenticity. For access to prerecorded and streamed concerts by the Orquesta Filarmónica de Bogotá visit https://espaciofilarmonico.gov.co/ My Interview with Maestro Zuluaga is below, click the “CC” for English subtitles!)