¡Printing the Revolution! at the Frist

versión en español aquí: https://www.musiccityreview.com/9697

Since the end of June and continuing through the end of September, the Frist Museum has had a wonderful exhibition of social and

political activism originating in the Chicano civil rights movements in the 1960s and 70s, described by adherents as “El Movimiento.” The term “Chicano” was once a derogatory term for people of Mexican heritage, is now claimed as a celebration of unique cultural identity. The exhibition, taken from a broader collection in the Smithsonian American Art Museum and titled ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now, creates an extensive and complex set of 5 sections that depict Latin American identity and artistic activism for justice and human dignity throughout the world.

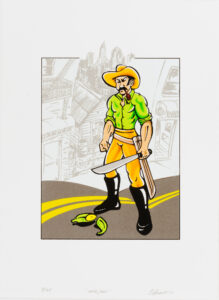

The first group of works is titled The New Chicano and emphasizes the hybrid identity of this population. Carlos Almonte’s Vale John, from the portfolio Manifestaciones (2010), shows a powerful campesino (farm hand) in the middle of an urban street standing over a plantain. He is in front of what seems to be a Caribbean style home slotted between a bakery and a grocery store, in front of a skyline that might be either Chicago or New York—the two worlds of the Dominican Republic and the United States collide.

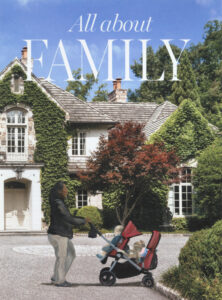

Another work in this section is Jay Lynn Gomez’s All About Family (2014) is one of a series which brings into view the domestic laborers that support the ideal of suburban tranquility in the United States. This is accomplished through painting images of the laborers onto photography appropriated from magazines depicting affluent lifestyles. Most powerfully, the anonymous nature of the laborer is maintained through a blurring of the worker’s faces here and in other works in the series.

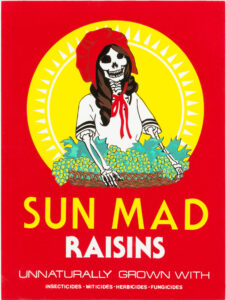

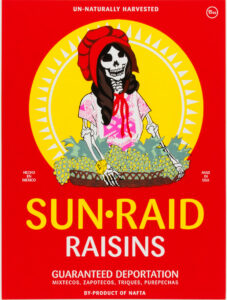

The second section, Urgent Images, confronts political and social issues directly with examples that participate in the fight for working conditions for migrant laborers, and engage with issues surrounding migration and deportation and, especially, police brutality. One such example is Ester Hernandez’s Sun Mad (1982) in which the traditional Sun Maid raisin package is redrawn to “unmask the wholesome figures of agribusiness” and focus instead on the polluted water and pesticides that unhealthy farming practices placed into the water in California’s San Joaquin Valley.

A quarter of a century later, Hernandez reimagined the original image in a criticism of I.C.E., the United States’ Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency. While Sun Mad shows a skeleton (calavera) in the traditional huipil, the Sun Raid version adds an ICE wrist monitor.

The third section shifts the focus to Changemakers with portraits of advocates for political, civil, and human rights. Many of these works feature the bright colors and bold lettering of pop art on important figures such as Frida Kahlo and revolutionary Emiliano Zapata. Rodolfo O. Cuellar’s Selena, A Fallen Angel (1995) was created the year she was tragically murdered. During her short career she created an inspirational movement on both sides of the Mexican border and an explosion of interest in Tejano music; a movement that all but fell apart on her death. Here Cuellar monumentalizes her appearance on her best-selling album, Amor Prohibido.

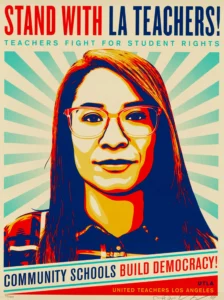

A more recent example is Ernesto Yerena Montejano’s Roxana Dueñas from a commission by the Teacher’s Union of Los Angeles to provide an image to support their demands for improved working conditions.

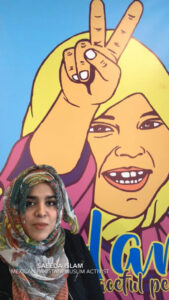

The fourth section, Digital Innovations and Public Interventions, shows Chicano artists’ work in reaching an ever-broader audience. For example, Xico González’ Salam (2019) employs augmented reality by overlaying a video image on a young Palestinian girl brandishing a peace sign. The result is an intertextual expression with an oral history of the Mexican Pakistani activist Saeeda Islam who discusses her dual identity as both Muslim and Mexican.

The final section, Reimagining National and Global Histories, which, as the program describes, “shows Chicano printmakers expressing solidarity for people around the world.” Specific topics engaged include the genocide indigenous peoples, the Cuban Revolution, the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Movement and Apartheid.

The exhibition, as a collection seen together, has a couple of powerful characteristics. For instance, the different sections of the exhibition overlap in many ways pointing to the multivalent expressive strengths and goals of the artists. Further, seeing these works in a chronological grouping (and the pieces displayed in this article are only a handful of the many pieces on display at the Frist) brings an important recognition to the long and steadfast ideals of the artists of el movimiento. It is a powerful introduction to the long tradition and continuing evolution of Chicano Art in the United States, a tradition that continues to seek, and effect, the changes needed for progress, justice, and human rights in our democracy.