From the Nashville Film Festival

Nashville-related Music Films

For this list I’ve curated films from the festival that are both short and feature length with Nashville-related subject matter. From denial to lament, nostalgia to excitement, as a collection they reflect some of the broader community’s perceptions of, and reactions to, the changing character of Music City and its almost unprecedented growth. In some ways, what you don’t see here remains part of the problem.

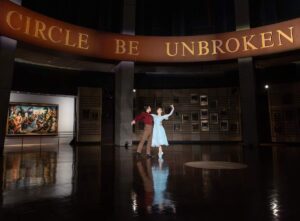

Chet Atkins’s “Jitterbug Waltz” Inspires a Nashville Ballet Performance in the Hall of Fame Rotunda

First up is Chet Atkins’s “Jitterbug Waltz” Inspires a Nashville Ballet Performance in the Hall of Fame Rotunda. Created in celebration of the centennial birthday of Nashville-based and Tennessee-born guitarist Chet “Mr. Guitar” Atkins, the Country Music Hall of Fame and the Nashville Ballet collaborated in a filmed ballet performance to his “Jitterbug Waltz” in the Hall of Fame’s Rotunda. The dance, envisioned by Museum trustee David Conrad and choreographed and co-directed by Nick Mullikin of the Nashville Ballet, brings to life the central pair of dancers in Thomas Benton’s famous painting “the Sources of Country Music.”

The film opens on the painting in its permanently home in the rotunda, and soon zooms out to see our dancers in stylized Western ware (costumes by Mycah Kennedy). Their dance seamlessly merges classic ballet technique with the subtle references to the innovations of Martha Graham’s Appalachia. Dancers Shaiya Donohue and Cassandra Thoms are simply fetching, providing the charming smiles and inestimable physical grace to accompany the cascading arpeggios of Atkin’s work. The cinemaphotography by Chad Driver takes advantage of the rotunda, producing whirling, dizzying shots as the camera, dancers, and background seem to twirl together, playing out a mesmerizing courtship.

The result is a little bit different from what we have come to expect from the Nashville ballet, an organization who, apart from the annual obligatory escapism of the Nutcracker, have been relentlessly political in choreography and expression. Here, however, the expression is much more escapist, in an enchanting, utopian, nostalgic and Romanticized view of America’s and Tennessee’s past, flush with white cisgender privilege and grace. It is a beautiful but reductionist image of our past that the museum itself has been trying to deconstruct recently with exhibits like the Night train to Nashville. Even so, I watched the video several times because it is simply beautiful.

Legacy in the Making: The Bluebird Café

Director Dominic Gill’s Legacy in the Making creates a similar nostalgic view of Nashville in the documentary of the creation and history of The Bluebird Café. The narrative describes how the Bluebird process works, the auditions, the competition and how the in-the-round format was created to create an atmosphere that privileges songwriters. It is a story replete with heroes and little to no antagonism. Further, most of the discussion is focused on describing the Café as a small-town restaurant in the songwriting community instead of the role the Café has at the center of a music industry; a place where an artist will go to perform and land a contract. Like the Whisky a Go Go was for Hard Rock in California, Studio 54 was for Disco in New York or the American Bandstand was for Rock and Roll in West Philly, The Bluebird is ground zero for country songwriters in Nashville.

The only real recognition of its place in the industry is the use of chairbacks labeled with artist names coupled with chapter titles. We see Tom Waits paired with the chapter “Listen to Your Voice,” and Bonnie Raitt appears with “Amplify Your Voice.” There might be a little tension in the pairing of Taylor Swift with the “Preserve Your Voice” chapter, given that Swift was “discovered” at the Bluebird, but has since done anything but preserved a country, singer-songwriter voice. However, that tension is undeveloped. The video celebrates and romanticizes an industry that is still replete with issues of equality, diversity, and fair compensation practice—issues readily apparent throughout the video but left unaddressed. That said, for the Nashville tourist, the recently arrived artist with stars in their eyes, or perhaps a new employee orientation at the Bluebird, this film is perfect.

The Day the Music Stopped

Unlike Legacy in the Making, and Chet Atkin’s Jitterbug Waltz, Patrick Sheehan and Demetria Kalodimos’ The Day the Music Stopped is a tragedy with a large collection of antagonists in its complicated depiction of city history. From floods, to bombings, tornados, to civil unrest, to global epidemics, to (a lack of) corporate competition, the story ascribes the closing of the iconic Nashville night club Exit/In to an incredible number of forces. This dive style punk club is the primary representative of the thriving alternative scene (alternative to country) in Nashville. Exit/In has, in the last fifty years, garnered a national reputation as the place to rock out on Saturday night in Music City. Since 1971 artists like Johnny Cash, Etta James, the Police, REM and many others have appeared there as well as professional wrestling and comedy (Steve Martin). Simply put, independent rock existed there and in Nashville long before Jack White ever left Detroit.

After a slow exposition that places the club in a historical context within the city, and a narrative describing many of the troubling societal events that have happened since 2010, without much explanation of each event’s relationship to the club’s dilemma, the film leads us to understand that the ultimate difficulty comes down to economics—the inability of the independent club to survive in the context of these issues and changes, more generally, in modern society and the music industry without (allow me to clutch my pearls) “selling out.” These are troubles that have and will continue to confront independent clubs across the country, whether it be 930 in D.C., Tower Theater in Philadelphia, the 40 Watt Club in Athens, or the Exit/In in Nashville.

From a broader perspective, there is a shelf life to any youth movement simply because folks grow older. It is worth noting that many of the characters you see in the film have reached or are already significantly north of the transitional and “untrustworthy” age of thirty. At one point in the film, a guitarist from Diarrhea Planet (a band featured widely in the film as the most prominent group on the scene) pleads with the crowd to be careful as what appears to be his teenage son surfs: “Do not fucking drop him!” This is parenting, the opposite of carefree youth. Indeed, the band was found 15 years ago in a dorm room at a local, private, and very expensive, Christian university. The idea of selling out has always been relative.

Also, a half century worth of longevity inevitably brings challenges. Granted that many of Nashville’s challenges result from exorbitant growth rather than decay, a place like the Exit/In and its community can only last so long before it either adapts to circumstance or succumbs to it. Operators (and heroes) Chris and Telisha Cobb may rue their decision to relinquish control of the venue, but this might be the only way that the institution could survive.

As a sell-out to the firm A J Capital Partners (a subsidiary of Live Nation—the Evil Empire), Exit/In may have lost some of its independence, but I see on the calendar that Amanda Shires will appear there in October, “Off the Record and Untamed” and in the face of her ex-husband and darling poet of mainstream country, Jason Isbell—what could be more Rock and Roll than that? Whatever happens with Live Nation and the Rock Music industry, whether or not their corporate, dominating trust will be allowed to continue to choke competition and rebelliousness to death, this is a beautiful film that will be sad, nostalgic and fun to watch for anyone interested in Rock, the history of Nashville in the early 21st Century, or simply feeling young and rebellious again.

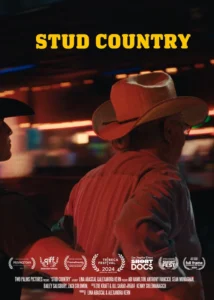

Stud Country

Finally, I chose the last film, Lina Abascal and Alexandra Kern’s Stud Country not because it takes place in Nashville, but because it presents a different way that a distinctly country and Nashville-based tradition may be employed to celebrate diversity. The film’s subject is an event, described as “…the largest queer country western line dancing event in America, which was created to preserve Los Angeles’ little known 50+ year queer line dancing tradition.” It provides an intimate take on the impact that safe spaces may have on a community and also the impact that occurs when those spaces are taken away, here through gentrification.

Perhaps the greatest aspect of the film is the intergenerational informants Sean Monaghan, a younger participant on the scene, and Anthony Ivancich, a dancer with a much longer history. In his introduction he describes his 50-years of experience as a queer dance teacher at Oil Can Harry’s in Los Angeles. Oil Can Harry’s one of the first publicly gay dance bars, opened in 1968 and closed its doors in 2021, this for many of the same reasons discussed above with the Exit/In. Ivancich’s story is important because he reflects on experience and the fact that people are resilient and will find a way: “I know the kids are frustrated the club is going to close soon, but having already been through this, I know it’s just probably another stage.” The symbolism in seeing these two men twostep is excellent cinema.

Given the political climate in the state of Tennessee, and the hyper masculinity that often accompanies the Country music traditions here, it is difficult to imagine queer line dancing would ever take hold in Music City, but a quick google search indicates that there is a weekly lesson, related to Stud Country, ongoing at Turn Their Heads! Now that the Wildhorse Saloon has shut down (or as Luke Combs’ would have it, “reimagined”) perhaps there is room for this more inclusive model in the Music City?

In all, this group of films at the Nashville film festival revealed the complexity of our Music City in its traditions, its growth, its difficulties and some of its diverse perceptions. Yet, there is still so much work to be done. This is obvious in the simple near absence of BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Color) from all of these films set in Nashville—it is a lacunae that one might think will be addressed by the International Black Film Festival, also set in Nashville next month. One might note that we have a long history of separate but equal stuff in Nashville–it doesn’t work. In this new century, finding a way forward for everyone will be a challenge, but I think that the film makers are making an important contribution to the search.