from the Annals of Nashville's Diversity:

Mendelssohn, Huang, and Barnes at the Schermerhorn

Sometimes the best concerts give you no, or very little, indication of what is happening beforehand. This was the case with the Nashville Symphony’s presentation on April 11 & 12, unceremoniously titled “Mendelssohn’s Fifth.” While it did feature a wonderful performance of Mendelssohn’s Reformation Symphony, little emphasis beforehand was placed on the two excellent compositions by living composers (the composers were in the hall!), the inclusion of not one, but three visiting world-class artists (soloists including the NSO’s own Titus Underwood) as well as a remarkable guest conductor and director of the San Bernardino Orchestra in a most exceptional program showing distinct and ingenious approaches at blending the folk, the secular and the sacred with the classic. Given a time machine, I would have conducted interviews with ALL of these folks, but I digress.

The evening began with a performance of Joan Huang’s Tujia Dance (1994). Like many Chinese intellectuals of her generation, Huang was raised during the Chinese Cultural Revolution and “rusticated,” as a teen, that is, she was forced to take part in Mao Zedong’s “Down to the Countryside” Movement, which forced the children of urban intellectuals (the bourgeois) to perform heavy labor in rural settings. When this so-called “Revolution” subsided, she was among the first to attend a reopened Shanghai Conservatory.

Her Tujia Dance originated in a fieldtrip she took from the Shanghai Conservatory to visit the Tujia people in Hunan Province and her effort “…to produce a sonic portrayal of the Tujia people’s rural life.” The sound of the delicate celeste and harp stood out for me. Huang’s rhythmic organization is reminiscent of Stravinsky in its layered and elaborate structures, all handled quite well by Tennessee-bred Maestro Anthony Parnther. It seems that he has been championing Huang’s work for some time and we eagerly await a recording!

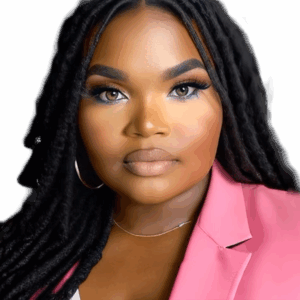

Next up was Jasmine Barnes’ Kinsfolknem, (pronounced “kinsfolk and ‘em”) a “celebration of family and extended family gathering,” which highlights “…the sound world of places and themes surrounding Black family gatherings.” A composer, educator, and vocalist with no fewer than five full-length stage works to her name, Barnes is a member of the “Blacknificent Seven,” a mutually supportive collective of composers that formed during the pandemic. (I am proud to say that, including the current review, works by 5 of these 7 composers have been discussed/covered in the pages of MCR: covered composers include Jessie Montgomery, Shawn E. Okpebholo, Nashville’s own Dave Ragland, Carlos Simon, while we still await works by Damien Geter and Joel Thompson in the Music City).

Barnes’ Kinsfolknem is a beautifully conceived composition which seems to engage with the long history of third-stream works. Apart from Ellington, Still, and perhaps Gershwin, one can hear some Gunter Schuller in the conception. Most remarkably though, and this is probably a result of the “Kinsfolk” aspect of the composition, there is a Milhaudesque (I’m thinking of the opening to La Création du monde) and Dixieland democratic sensibility to her composition, a collective perspective sourced in the early identity of New Orlean’s Jazz– both in reedy timbre and in it’s a sense of collective improvisation. This sound is set within a Sinfonia concertante in which an ensemble of four woodwind musicians engage in dialogue amongst themselves and with the broader orchestra. This stellar ensemble in Nashville included the brothers Anthony (flute) and Demarre (clarinet) McGill, native Tennessean Andrew Brady (bassoon) and Titus Underwood (oboe).

Barnes’ first movement, “The Sunday Dinner,” brought out the blue napkins to go with the china, emphasizing not only the soloist abilities of the ensemble, but their abilities to blend, lead and join the broader orchestra. This was when I remembered the fact that 3/4s of the ensemble held a Principal Chair at a major symphony orchestra at some point. This synthesis was aided, of course, by Maestro Parnther’s gentle but clear direction towards that rich, stunning sound.

Hometown favorite Underwood’s part in the second movement “The Repast” was played with his characteristic rich tone and easy, fluent technique. The finale, a ragtime cum bebop “Reunion,” was exciting, fresh, exuberant, and well-deserving of the standing ovation. Given her remarkable ability to construct clear and exquisite moments with an orchestra, one can understand Barnes’ emphasis on vocal (the operatic, dramatic and biblical) compositions. However, given her demonstrated genius for smoothly merging dissimilar 20th century American styles within an absolute formal organization (the Sinfonia concertante of all things!), I, for one, want to hear more of her instrumental works as soon as possible.

After intermission, and all of this wonderful 20th and 21st Century music, we returned to our seats to hear the Felix Mendelssohn’s romantic 5th Symphony, “the Reformation.” Mendelssohn, part of a prominent Jewish family that had baptized the composer into the Lutheran faith, this symphony relays the heroic victory of Protestantism through the thematic transformation of the old chorale “Ein feste Burg.” Parnther handled Mendelssohn’s delicate polyphony in the first movement’s appearance with great care, ensuring precision and balance in the Palestrinian counterpoint. The bright, exuberant scherzo led to a lyrical slow movement where Peter Otto’s marvelous section gave us a gorgeous melodic line. The finale and the dénouement with its victorious return of the chorale hymn, topped off the night with yet another moment of breathtaking beauty.

The Nashville Symphony has, for some time, demonstrated a dual mastery, an ability to create powerful interpretations of the most recent works, even as they refresh, remake, and rejuvenate the masterpieces of old. As such, this program played to their unique strengths. But even more so, as I drove home to Antioch, along Murfreesboro road (route 41), through the melting pot of South Nashville, past the Coptic and Christian churches, the murals, the burrito trucks, the Ethiopian coffee houses, the Chinese Restaurants and all of the beautiful diversity, I realized that Maestro Parnther’s program as reflective of “Nashville” as anything else scheduled this season at the Schermerhorn—he still knows “his old stomping ground.” The Nashville Symphony will perform again at the end of the month with a Tchaikovsky Celebration starring Oliver Herbert (cello) and Tony Siqi Yun (piano). Tickets available here.