Martha Graham returns to Nashville—at least in spirit!

On January 31 and February 1, as part of their amazing International Dance Series Season Package, the Tennessee Performing Arts Center (TPAC) is presenting the Martha Graham Dance Company. Founded in 1926 by its namesake, and celebrating their 100th anniversary with a three-year series of performances, the company is the oldest, and oldest integrated, dance company in the United States. Thus the current production is a somewhat Janus-faced expression of Martha Graham’s impact with two works (Appalachian Spring, and Immediate Tragedy) looking back to Graham’s classic choreographies while also presenting two choreographies of now and the future (We the People, and Cave) pushing Graham’s innovations into the 21st century. Quickly becoming the destination in the American (re. United States’) South for contemporary dance, Nashville is in for a real treat with this production.

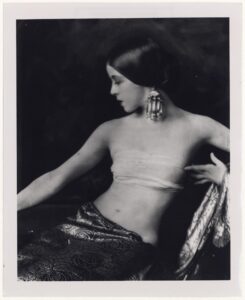

It is difficult to overestimate the impact that Martha Graham has had on American Dance. Born in Pittsburgh, PA in 1894 and trained in the Denishawn School of Dance in California, she learned the exoticism of the day (Egyptian, “Oriental,” “Spanish”). Some of this she would demonstrate in her choreography for the film The Flute of Krishna (1926). She would appear in the vaudeville circuit and have her Broadway debut in the Greenwich Village Follies Review in New York. She then found employment at the Eastman School of Music in 1923. Three years later she established the Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance where she began to embrace the general aesthetic expressions of the modernist movement. In 1930 she stated:

“Like the modern painters and architects, we have stripped our medium of decorative unessentials.”

Her dance, from this inspiration, sought to express human feeling in the abstract, taking influence not only from the American Pioneer spirit, but also from the gestures of Native American and black cultures. These influences were of a colder, bracing, and objective approach that stripped the style of its sentimentalism. In a similar way, she wanted to redefine the female body in terms of rigor, power and intensity as opposed to the standardized beauty of the Romantic and Impressionist eras. The impact on the style was significant. Under the dancer’s feet, the floor would be a drumhead. The dancer’s breathing would be a process of contraction and release; a process upset in the passion of emotion. Generally, the music would be defined more in terms of its rhythm than its melody.

From 1929 through 1938, across the Great Depression, Graham composed twenty-one works for her then all-female company, including 36 of her own solos, most of which overtly carry an American topic objectively emphasizing ritual and identity. For the most part, Graham avoided contemporary political topics, but one of the exceptions to this include Immediate Tragedy (1937), which deals with the horrors of war and the impending threat of fascism (the Spanish Civil War had begun in 1936).

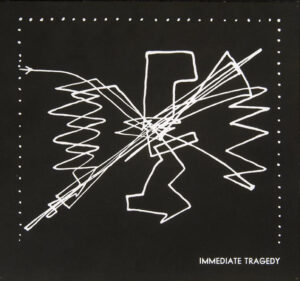

Immediate Tragedy (1937)

Immediate Tragedy’s music was composed by the great and eccentric composer Henry Cowell who wrote the score while serving time in San Quentin Prison on a morals charge. In prison, he was given Graham’s notes on the work’s mood, tempo and meter but no ideas with regard to time—how long a movement or section should last. Confronted with this huge difficulty he created an “elastic form” by writing phrases of varying length that could be fit to matching dance phrases. For her part in the collaboration, Graham’s dance was inspired by Pasionaria, aka Dolores Ibárruri, a hero of the Spanish Communist Party that would ultimately fail in its resistance of Franco.

One of Graham’s contemporaries, José Limón, described Graham’s performance of Immediate Tragedy at its premiere in Bennington, Vermont as a “…consummately sinuous torso, the supple beautiful arms, the hands flashing like rays of lightening.” John Martin, critic for the New York Times (August 15, 1937), described the dance as a “stunning achievement” whose message extends beyond its immediate context, “…let it be said at once that this will be a moving dance long after the tragic situation in Spain…for it has completely universalized its materials.” However, because her company never took up a performance of the dance, the choreography and its music are now lost.

However, cultural historian Neil Baldwin recently discovered a letter between Graham and Cowell describing the choreography, where Graham described her experience dancing it as “I feel driven, compelled and energized, […] I felt that I was dedicating myself anew to space, and that

“inspite of violation I was upright and I was going to stay upright at all costs.”

Perhaps even more miraculously, a role of film containing photographs from the premiere, taken by Robert Fraser, has emerged which gives poses, and their order, from the original dance (one example is in black and white, above). From these, Choreographer Janet Eilber and the contemporary dancers of the Martha Graham Dance company assembled a choreography from these images. (Documented here) Further, in constructing the choreography, they employed Arch Lauterer’s sky map of Graham’s dance (a map which traces from above the movement of Graham throughout the dance). For the music, Christopher Roundtree created a new “open” score based on the Baroque dance Sarabande whose rhythms we know characterized Cowell’s original score, but also with parameters to accommodate its performance over zoom (the entire project was completed during the pandemic). What Nashville’s performance might have in common with the pandemic era performance remains to be seen! Original performance here

Appalachian Spring (1944).

Across the 1930s Copland and Graham were simultaneously and separately developing an artistic vocabulary for the expression of Americana. Copland’s work, particularly, was built on a relatable and accessible language whose purpose was to connect with the general public. By the time he began to work with Graham, he had enjoyed widespread, mainstream appeal for his ballets Billy the Kid and Rodeo. The way that Graham and Copland worked together, this ballet perhaps best clarifies the artistic intentions and Americana style behind both artists’ work, resulting in a work that would become central in Graham’s repertoire, and (especially when arranged into an Orchestral Suite), one of Copland’s most memorable works.

The setting of Appalachian Spring is a wedding on the American frontier, yet the dance itself functions not as part of the ritual but instead as a character soliloquy. With each character’s solo dance, the action stops so that the dance may express individual character and emotions contrasted sharply with the clarity and spaciousness of an American frontier. The expression is beautiful and yet quite sophisticated. In the Bride’s two solos look, for example, not only for her bliss at the idea of marriage but also her apprehension of her future to come. Throughout, look for the subtle influence of country dancing on Graham’s choreography and listen for the wide open spacing of Copland’s orchestra.

We the People.

Appropriately, the production offers a 21st century take on Americana and the American identity with We the People, a choreography by Jamar Roberts, who is a former dancer and resident choreographer for the Alvin Ailey American Dance theater (who we saw in Nashville just last year). The music was written by Rhiannon Giddens and arranged by Gabe Witcher. Giddens, a Greensboro NC native who is known for her eclectic folk music, just performed with the Musicians of the Silkroad Project at the Schermerhorn last November. Roberts has characterized the ballet as: “…equal parts protest and lament, speculating on the ways in which America does not always live up to its promise. Against the backdrop of traditional American music, We The People hopes to serve as a reminder that the power for collective change belongs to the people.” While many things regarding the American identity appear to have changed, the juxtaposition of the two works (Appalachian Springs and We the People) might just prove to be even more powerful.

Cave.

Martha Graham was an innovator, taking cultural expressions and incorporating them into her developing artistry often in the face of the taste of her critics. Cave’s first conception occurred when Daniil Simkin, an internationally recognized ballet artist suggested to the Graham dancers that a work might take inspiration from the techno club scene. Israeli choreographer Hofesh Schechter was invited to create a prelude to the idea in a dance which has been described as combining “the transcendent with the communal.” Like Graham’s works, Simkin’s is not immune to controversy.

A rather grumpy and confounded Gia Kourlas of the New York Times described Cave in 2022 as “…little more than manufactured fun, […] little more than a series of flash mobs, in which the men increasingly threw themselves into the action — [while] the women – bouncing, undulating and spinning, transformed into a coven of spirits.”

In 1945, one Norman Nairn wrote of Appalachian Spring in the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle “Martha Graham and her dance company came to the Eastman last night and left a large audience completely bewildered… I presume the movements [in Appalachian Spring] were expressive of something, but of what I wouldn’t know. Presumably it was their introduction to the modern dance, the new form as evolved by Miss Graham. If there was one person in the whole auditorium who understood what it was all about, diligent search failed to unearth that person.”

Indeed, due to the work of the great Lula Naff, Graham’s company, including Erick Hawkins (pictured above) came to Nashville and performed at the Ryman (the “Carnegie of the South”) in 1949 at the height of segregation. The Nashville Banner announced ten days before that “Some 200 seats in Section 7 at the Ryman Auditorium “…have been reserved for students of A&I State College, Meharry Medical School and Fisk University.” It was an event for the entire city and memorable enough for both Graham and Tennessee that she returned to perform at the Tennessee Tech gymnasium in Cookeville the next year. Writing for the Banner (2/19/1949), critic Sydney Dalton characterized the troup’s performance in Nashville as “…often its meaning and point were anything but clear. At times it was dull and its exaggeration smacked of the grotestque.” It is a remarkable fact that the Martha Graham Dancers have consistently confounded and bewildered critics for nearly a century. I, for one, can’t wait for my opportunity to be bewildered, TPAC is to be commended for bringing the troupe to town! The Martha Graham Dance Company appears at TPAC’s Polk Theater on January 31-February 1. Tickets are available here.