From Nashville Ballet

Not a Dance Macabre, But a Ballet with Identity

(Versión en español aquí)

How fortunate are those whose memories reveal themselves with clarity and movement. Even more fortunate is the one capable of replicating them so they may endure in collective memory. My guitar teacher used to tell me, “If you managed to see two delicate dancers twirl, my performance would have fulfilled its purpose.” That same purpose inspires an artist’s strokes and a composer’s verses—that ambitious desire to make imagination tangible.

And those dancers are not just a specter of their creator; their dance is reciprocal and transforms materiality into movement. Each step shapes rhetoric into a three-dimensional object, yet the audience retains autonomy in their interpretation. In that instant, remembrance completes a cycle, impregnating the scene with each individual’s history. Behind the scenes, onstage, and in the seats, a tapestry has been woven in tribute to memory—vivid and adorned with flowers, like the traditional chiapaneco attire.

From the intricate arabesques of the masks to the heartfelt altar at the center of the set, Día De Los Muertos is a production that stands out for its attention to detail. The essence of this tradition, narrated through the artistic inspiration of Diego Rivera, Frida Kahlo, Carlos Chávez, and Lola Álvarez Bravo, begins as a great success in script creation. Including folkloric elements like mariachis and alebrijes, along with the mystical figures of La Catrina and La Bruja, added a magical touch to the story. Maria Konrad and the artistic and production team elegantly and emotionally honored Mexican culture.

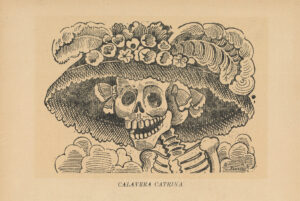

I may miss many elements, but you can already imagine the creative abundance in this show. I’ll start with La Catrina, as she is one of the main axes, not only in the production but also in her significance for Mexican culture. Although this character is inspired by Diego Rivera’s rendition in his renowned work “Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in the Alameda Central,” the figure itself is based on “La Calavera Garbancera” by Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada. The illustration is a critique of Indigenous chickpea vendors who dismissed their heritage and pretended to have a higher social status. “Down to the bones, but with a French hat adorned with ostrich feathers,” Posada described it. In Rivera’s work, the character appears full-bodied with a suit matching the characteristic hat but with Mesoamerican details like the Quetzalcoatl (feathered serpent) scarf. Rivera gave her a special place among the 150 figures included in this masterpiece. La Catrina, as the artist renamed her, represents every human being who, stripped of their appearance, shares the same structure and the same end with their fellow beings.

Among the different dance styles included in the production, La Catrina took advantage of the classical ballet pointe technique to represent her stylized nature. Moreover, her steps were resonant enough to enhance the “idiophonic” quality of her bones. The character appears painted on a canvas during her creation process in what could be imagined as Rivera’s studio. There, the painter shares his artistic passion with Frida Kahlo while adding the final strokes until the figure transforms into a dancer, joining her movements to the romanticism of the scene.

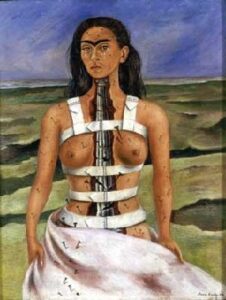

Frida Kahlo’s costume was also inspired by a piece of art—her self-portrait “The Broken Column.” This painting represents the strength of her body and soul, standing resilient despite having endured a near-fatal accident. The embroidered flowers on her skirt were replicated on Rivera’s costume, reinforcing the couple’s bond. Their movements were complicit and prolonged, flowing in perfect harmony. In the following scenes, composer Carlos Chávez joins with a carnival air, clumsy and awkward movements that reminded me of the renowned comedian Cantinflas. In contrast, photographer Lola Álvarez Bravo is light, flexible, and fills every space on the stage while capturing the best shots with her camera. To this celebration of life and friendship among artists, the mariachi group and folk dancers join. The performance is a mixture of jarabe tapatío and modern dance.

The musical selection for this ballet is another triumph; it merges traditional and mariachi music with electronic interludes. The soundscape also becomes cinematic with the modern contributions from Gustavo Santaolalla and guitar duo Rodrigo y Gabriela. The earthly realm seems fantastic enough; however, the altar in the set acts as a portal leading us to the world of eternity. I found the section particularly beautiful where the dancers represent each honoree’s preferences. One dancer skillfully dribbles a soccer ball before adding it to the altar’s offerings. Among these items are also the alebrijes, spiritual guides of zoomorphic nature whose purpose is to guide the soul’s journey. These magical beings transform into dancers of various colors and personalities, representing the qualities that make each mortal unique and unrepeatable.

In unity with the celebration of Día de Los Muertos and the music, the final cast member, La Bruja, emerges. The song of the same name, a popular son jarocho, has become the anthem of this popular festival. The lyrics are inspired by the legend of a seductive woman who preserves her corporeal form by drinking the blood of children and adults. The ballet’s climax is consolidated in this scene, where each character interacts with La Bruja and the subjectivity of death. The set darkens, and the traditional skirts emit colored lights, achieving a supreme effect with their dance movements. La Bruja’s costume also lights up, and a brilliant cluster of stars is revealed when the dancer extends her wide skirt. This moment of fantasy and emotion ingeniously captures the night of November 1st, when the streets are lined with candles.

The production concludes with a blend of overlapping voices, mentioning the names and ties of those who live on in each person’s memory. The dancers finish their movements, positioning themselves in a sort of portrait that once again evokes Diego Rivera’s muralist work. This final tableau comprises not only the artists on stage but artisans, musicians, designers, and technicians—all with an insatiable creativity and commitment to art, culture, and human remembrance as the essence of our existence.