From Our Far-flung Correspondents Series:

Yuja Wang, Andris Nelsons and the BSO Tackle the Turangalîla-Symphonie

On the weekend of April 12-13 I was able to attend a musicology conference on music criticism at one of those fancy schools just outside of Boston, MA. During my visit, I was lucky enough to be able to attend Maestro Andris Nelsons and the Boston Symphony’s production of Olivier Messiaen’s rarely performed Turangalîla-symphonie with Cécile Lartegau on the ondes Martenot and Yuja Wang at the piano (Nashville last performed it in 2018, review here). Part of the Boston Symphony’s “Music for the Senses” series and performed exquisitely by the BSO, Messiaen’s giant symphony is a wonderful exemplar of the French composer’s sophisticated style, his various expressive passions (spiritual Catholicism, Eastern philosophy, nature, etc) as well as his related musical passions.

The work’s premiere is stacked with historical meaning that deserves mention. It was commissioned by Serge Koussevitzky on behalf of the Boston Symphony in 1946, just after the Second World War and just five years after Messiaen had been released from the Nazi work camp in Zgorzelek, Poland. Messiaen, who by then had become a very well-regarded Professor of Composition at the Paris Conservatory, had written a theme for organ, Tristan et Yseult – Théme d’Amour (“Tristan and Isolde – Love Theme”).

During the same period, his first wife, (violinist Claire Delbos) began to suffer a long decline in health—exacerbated by a catastrophic hysterectomy that left her with a brain infection and complete amnesia in 1949. From that point she would have to be institutionalized until her death in 1959. It is said that, apart from touring obligations, Messiaen visited her every day.

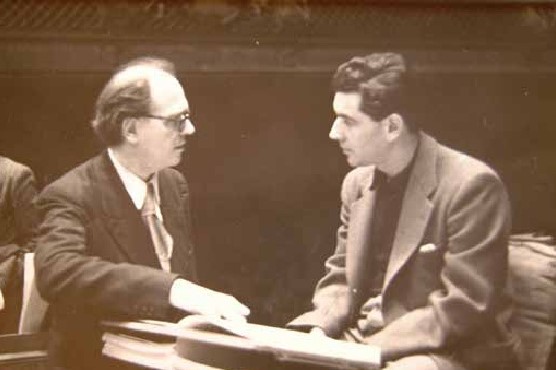

And yet, during the same period, Messiaen met and fell in love with Yvonne Loriod, a pianist and student of his composition studio at the conservatory. While the feelings were shared, they were not acted upon (Messiaen was a devout Roman Catholic and raising his son Pascal alone). Loriod described the situation as “…we cried for nearly 20 years until Claire died and we could marry.” Thus, instead of expressing his forbidden love, Messiaen composed monstrously difficult piano parts for the virtuosa Loriod, later stating that he allowed himself “…the greatest eccentricities in his scores because he know that she would master them effortlessly.” The Turangalîla-sinfonia , itself ten movements written for a huge orchestra, augmented percussion section , piano and ondes Martenot, was the central part of a tryptich that he developed out of his work on the Tristan und Isolde myth, and its piano part was written with Loriod in mind. It was premiered by the pianist and the Boston Symphony under Bernstein’s baton in 1949 (Koussevitzky had fallen ill). Famously and perhaps a little overtly jealous, on hearing the piece Pierre Boulez, who was also in Messiaen’s studio at the conservatory, called it “brothel music.” In Boulez’ defense, it is true that as opposed to Wagner’s guilt-ridden conceptualization of Tristan, for Messiaen the myth of Tristan and Isolde was an expression of the divine gift of physical and emotional love.

But the difficulties don’t only reside in the piano part. For example, Messiaen’s approach to rhythm is based on an organization built from duration instead of meter—an emphasis on the length of the notes instead of the recurrence of accent. These he adapted from Hindustani tālas. In the first movement, for example, the rhythms are based on the rāgavardhana, and lakṣmīśa tālas superpositioned on top of each other (these rhythmic organizations he also employed in the first movement of his Quartet for the End of Time). These were set against the powerful BSO trombones (Toby Oft and Stephen Lange) who were given the main theme of the opening movement (the “statue” theme). It was stirring, but not overwhelming—a difficult task and a complement to Nelson’s attentions to balance.

These rhythms, as well as other rhythmic devices (like the asymmetric augmentation of three rhythmic identities by the maracas, wood block, and bass drum in the third movement—kudos here to the BSO percussion section) and the perception of an organization that they create, even if the specifics of the organization that is beyond comprehension, are employed as allegory for the spiritual infinite.

Another source of inspiration was the Balinese Gamelan, for which the BSO prepared listeners with a wonderful preconcert demonstration by Gamelan Galak Tika. In the Symphony, the glockenspiel, celesta and vibraphone had a role that the composer described as very similar to the “East Indian gamelan.” It was delightful to watch Vytas Baksys (Celesta) and Jonathan Bass (Keyboard Glockenspiel) consult with each other and the score onstage, just before their third performance of the piece. Of course their performance came off without a hitch, but on Saturday night it seems that they were still earning things about the score!

On the ondes Martenot, Cécile Lartigau performed wonderfully, with an attention to detail that corroborates her international reputation as a leading interpreter on the instrument—a part traditionally performed by Loriod’s sister Jeanne Loriod. Turning to the piano, Yuja Wang, an international star and sensation in her own right, proved herself up to the task of a part that essentially expresses virtuosity for the collaborative artist. Never one to sidestep the opportunity to undertake a performance of monumental size, for the evening Wang stepped from her personal spotlight to engage with the rest of the ensemble in this monumental work.

Most important was the clear connection Wang maintained with Nelsons throughout the performance. On Saturday night, after a huge cadenza, a couple of members cheered (they knew better but couldn’t help themselves). The glance between Wang and Nelsons was precious, as if to say, “yeah, whew!” –one wonders if that is the version that will make the recording? As part of this, her presence on the stage was not as a soloist, but a collaborative artist. One of the things that marked her interpretation was a patient and masterfully empathetic relationship with the rest of the ensemble’s performance.

Out of curiosity, I have created a miscellany of interpretations of one of the most beautiful moments of the symphony (the last page of IV, “Chant d’amour”) featuring some of the most famous interpreters of Messiaen. The collection appears in the video below. Of the group, the clear best is (predictably) Loriod, she simply blends perfectly with the ensemble, and maintains a pace that gives the moment the relish it deserves. Ruraro seems just a bit too loud and slightly disconnected with the ensemble while Thibaudet’s chords seem too heavy. MacGregor’s interpretation is quite interesting (distracted by a missed note in the ensemble) and in Wang’s I believe the overall tempo (probably Dudamel’s choice) was too fast. On Saturday, in Boston, the moment, perfectly given by both Nelsons and Wang, gave me the chills. However, perhaps the most poignant moment of the evening was Messiaen’s great, final, orchestral crescendo. Wang’s hands simply rested in her lap as the rest of the ensemble rose to the heavens (and the audience rose to its feet). I am very excited to hear this recording and hope to return to Boston soon!

Next up (April18-20) for the Boston Symphony Orchestra is Mozart’s Symphony No. 33, Anna Thordvaldsdottir Anchora and Hilary Hahn performing Brahms Violin Concerto.