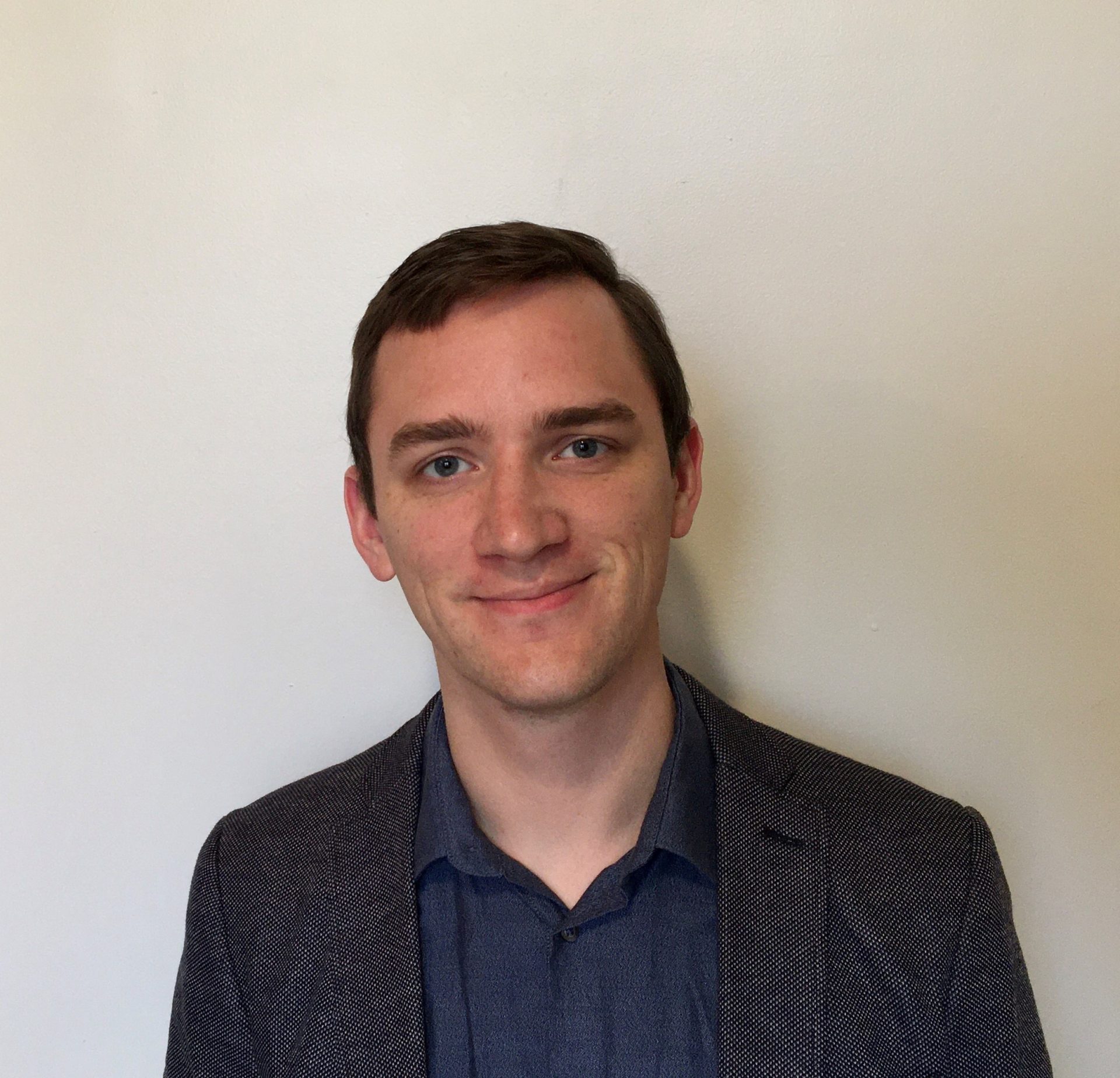

Wayne Marshall Does it All at the Nashville Symphony

Thursday night the Nashville Symphony featured the multi-talented Wayne Marshall who performed as the conductor, organ, and piano soloist in a jazzy program. Marshall has developed a long career that spans the globe performing in all three of those roles. He has held positions as Chief Conductor with several orchestras and has made dozens of recordings as a soloist. He is known for his interpretations of Bernstein and Gershwin in particular which made this program a real treat:

- Leonard Bernstein: Symphonic Dances from West Side Story

- Francis Poulenc: Concerto in G minor for Organ, Strings, and Timpani

- George Gershwin: Second Rhapsody for Piano and Orchestra

- Duke Ellington: Harlem

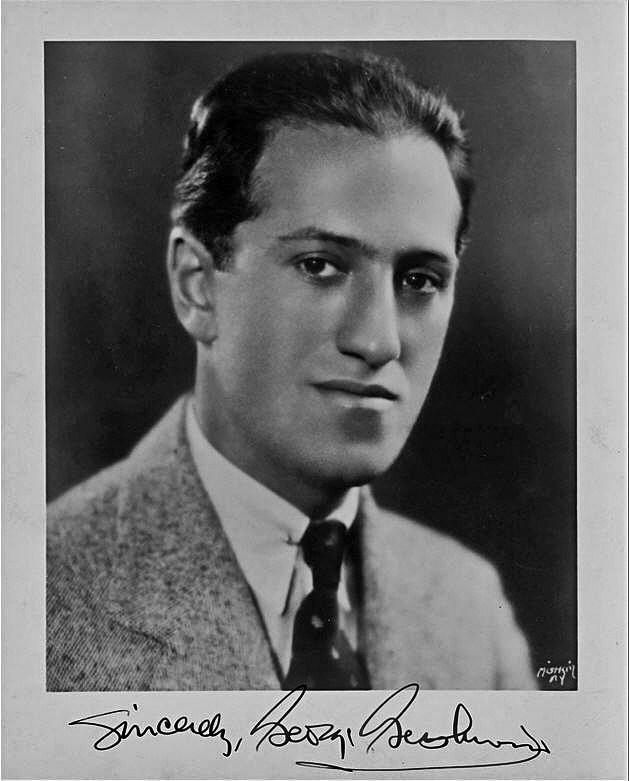

This program highlights the divide between the ‘Classical’ and ‘Jazz’ realms and showed that, perhaps, the divide is not as large as one originally suspects. Although each of the composers were born within a year of each other (except for Bernstein in 1918), they each operated in separate musical worlds. Bernstein had the classical credentials to bring Jazz and Broadway into the concert hall, Poulenc wrote ear bending harmonies with the simplest melodies, and Gershwin and Ellington operated almost exclusively in the jazz realm but created these unique symphonic masterpieces.

I was absolutely amazed in reading the program before the concert that this was the first performance of the Bernstein Symphonic Dances on a classical program for the Nashville Symphony. That fact floored me – especially for a group that prides itself on championing American music. Marshall mounted the podium without a score or a baton and proceeded with one of the faster tempos that I have heard. It even seemed to catch some of the players off guard, but eventually the group fell into the irresistible groove of Bernstein’s music. What struck me about this performance in particular is just how much fun this music is. That is one of Bernstein’s great gifts – his ability to infuse his music with his personality: big, brash, loving, fun, and occasionally raunchy. All these various moods were present throughout the performance and the audience loved to see the orchestra snap and shout “Mambo!” Marshall highlighted a lot of the syncopations in his conducting which occasionally created some timing difficulties, but also encouraged the orchestra to bring out the punchiness of this music.

Next up was Poulenc’s Concerto for Organ, Strings, and Timpani. The Nashville Symphony’s Martin Foundation Concert Organ is a beautiful instrument. Taking up almost the whole back wall of the Schermerhorn center, the instrument makes a big statement visually and audibly. Poulenc’s piece starts out exactly how I want an organ concerto to: loud strong minor chords on the organ contrasted with delicate strings. The concerto is about twenty minutes long divided up into seven differentiated tempo markings creating an arc of loud and powerful music, to softer middle sections, and back to a strong finale. Poulenc started writing the piece in 1938 around a time when he was rediscovering his Christian faith. Poulenc had never written for the organ before and to prepare for this commission he spent many months studying the masters of the instrument: J.S. Bach and Dieterich Buxtehude. What he produced has become one of the few standards for the organ repertoire that is from outside of the Baroque period.

Marshall played brilliantly. He seemed most at home sitting at the organ bench, as his playing and physical gestures were the most dynamic. The organ part is not too difficult, on account of Poulenc’s original commissioner of the piece, but Marshall brought out many subtilties and nuance in his performance. One way he did this was through his interesting choices of registration for the organ, filling in brass and woodwind gaps in the orchestra. The Symphony’s string section was a fantastic supporting partner in this concerto. Most of the players could not see Marshall from behind the large console of the organ, but they followed his playing expertly and matched his energy. To me Poulenc’s music is such an interesting oddity: phrases, melodies, and harmonies are all slightly out of place but for some unknown reason it all comes together in a beautiful whole.

During the intermission the organ was replaced with a piano for Gershwin’s Second Rhapsody for Piano and Orchestra. This piece, originally titled Rhapsody in Rivets, was originally borne out of George and Ira Gershwin’s music for the film Delicious. Not as renowned as Rhapsody in Blue, which just celebrated its’ 100th anniversary, Gershwin’s Second Rhapsody is a fantastic piece showing his compositional development. Gershwin himself said that the Second Rhapsody was “in many respects, such as orchestration and form, it is the best thing I have written.”

The Nashville Symphony played this piece exceptionally well Thursday night. Gershwin’s writing seems to be a lingua franca for the group. Crescendos swelled to their peak almost taking me out of my seat. Marshall’s playing was enthralling as he jumped between conducting and playing, sometimes literally, making it back to the piano just in time. The only issue of this piece was the piano was placed, with its lid off, with Marshall’s back to the audience. This is standard placement for when a conductor leads from the piano, but it caused the sound of the piano to occasionally get lost in the thickly orchestrated score.

Last on the concert was Duke Ellington’s Harlem, a piece that I was unfamiliar with from a composer whose works I deeply admire. Duke Ellington shaped and molded our conceptions of the Jazz sound and is one of the great fathers of American music. With over a thousand compositions, many of his works have become standards of the jazz repertoire and his music has expanded into the larger cultural consciousness. To transcend your area of expertise in this way and gain a wider cult

ural significance is a rare accomplishment, only achieved by the greatest of the great: Yo-Yo Ma, Michael Jordan, Steve Jobs, etc.

Harlem was originally commissioned by Arturo Toscanini and Ellington wrote two versions. The first for Jazz Band was premiered at the Metropolitan Opera House in 1951 and the second was scored for full orchestra, with the orchestrated help of Luther Henderson, was premiered at Carnegie Hall in 1955. Toscanini never ended up conducting this piece, much to my disappointment to hear the old great Italian Maestro conduct jazz! The orchestral version adds five saxophones to the traditional instrumentation. Instead of sounding like an orchestral piece with added saxophones, like Ravel’s Bolero, it sounds more like a jazz band and an orchestra combined into one, which was Ellington’s aim, as he called this a “Concerto Grosso for our band and the symphony.” This trend of blending the Jazz and Orchestral ensembles is something that Jazz/Classical composers like Wynton Marsalis have continued with pieces like his Swing Symphony.

In Ellington’s memoir Music Is My Mistress he wrote a programmatic note saying “[Harlem] has always had more churches than cabarets. It is Sunday morning. We are strolling from 110th Street on Seventh Avenue, heading north through the Spanish and West Indian neighborhood toward the 125th Street business area. Everybody is nicely dressed, and on their way to or from church. Everybody is in a friendly mood. Greetings are polite and pleasant, and on the opposite side of the street, standing under a street lamp, is a real hip chick. She, too, is in a friendly mood. You may hear a parade go by, or a funeral, or you may recognize the passage of those who are making our Civil Rights demands.”

When this program was originally announced Harlem was the opener of the concert, but I am happy that they moved it to the end. Its language is so enthralling, and its style is so clear that it made the most successful impact as a piece that night. The demands on the winds and brass players are immense: screaming trumpets, wailing trombones, and swinging reeds are called for throughout. The percussion section was the backbone of the piece, keeping everyone in time and eventually having an improvisatory section at the end. The ending felt like a real celebration and the audience was buzzing with excitement as they left the concert hall.