The African Company Presents Richard III: Unbelievably True

For their Spring Shakespeare presentation, the Nashville Shakespeare Festival did a staged reading of Carlyle Brown’s play The African Company Presents Richard III. Based on true events, the play is about an African American-run theater company in 1821 New York City, which is successful among the Black community, and is drawing in whites as well (who, ironically, are seated in a separate area in the back). Their latest success is a presentation of Richard III. But Stephen Price, the white manager of the Park Theatre, dislikes the idea of any competition between his production of Richard III and theirs, especially since his production is soon to premier, starring the famous British actor Junius Brutus Booth (this celebrity was a mentally ill alcoholic who, among other things, wrote a prank death threat to President Andrew Jackson, and whose son assassinated Abraham Lincoln). Price gets police cronies to shut down the African Grove Theatre over fire-code violations. Instead of allowing themselves to be defeated, the African Theatre decides to find a new location for their performances: a hotel ballroom right next to the Palace Theatre. Much of the play is spent on interpersonal tension in the African Theatre as they prepare for their production of Richard III in the new space and as an open act of defiance.

Besides the straightforward market competition between the two shows, Price views the production of Shakespeare by Blacks as presumption and culturally dangerous: it’s rather difficult to maintain the argument of racial superiority when the “inferior” race is producing popular productions of high art. As a sort of prologue, the poem “We Wear the Mask,” by Paul Laurence Dunbar (We Wear the Mask by Paul Laurence Dunbar | Poetry Foundation) is recited, emphasizing the later discussion of what it is to play a role in a play when you already have to play a role in your everyday life (For more discussion of this element in the play, see the MCR Interview with Direction Lawrence James:The African Company Presents Richard III: Interview with Director Lawrence James – The Music City Review).

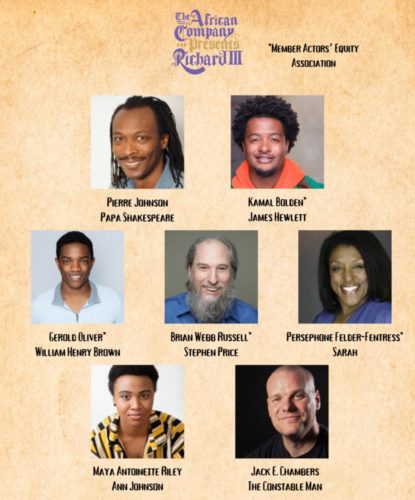

After the prologue, the villain of the piece, Price, comes on stage to speak to the audience of his theater on its opening night, and explain that the disturbance caused by the Black theater next door is now over and its culprits are going to jail. The contemptuous open nineteenth century racism of his speech is an effective, shocking way to begin. It’s followed by a scene occurring two days before, as members of the African Company meet for rehearsal. They talk about their latest successful performance and we are introduced to the romantic tension between Jimmy and Ann, who play Richard III and Lady Ann. This play is rather an ensemble piece, with only seven characters and a pretty even dispersion of dialogue (The Constable Man, a pawn to Price, is the only minor role).

There is some direct comedy in the play: after complaining about Lady Ann’s fickleness in Shakespeare’s play, and the implausibility of her giving in to Richard’s wooing, Ann has a freudian slip in rehearsal with Jimmy, revealing her true feelings for him.There’s a witty bargaining scene between the head of the African Company, Willie, and Price, in which Willie wins the battle of wits but causes Price to determine to shut down the new production with the help of the police yet again. Jimmy and Ann argue and she decides to quit the production, and for a portion of the play the characters look for her. When she’s found, Papa Shakespeare, the rather eccentric older actor and drummer, acts as a go-between between the bickering couple, openly altering their messages in an attempt to get them together.

Many aspects of being Black in nineteenth century America are examined, from discussions of their acting talents, to their daily lives working for white people, and reminiscences about their pasts in the West Indies. The play is balanced: the villainy of the manipulative Price is shown to be weaker than the enterprising spirit of the African Company, whose resilience against overwhelming setbacks is the same continuing spirit that led to the Civil Rights Movement.

I saw the play at the Darkhorse Theater, February 22, and it lasted around two hours, with a ten minute intermission. As a staged reading, this play had no props and a simple stage design: five chairs in a line centerstage facing the audience, and six stools in the back for the actors to seat themselves while their characters were off-stage. The actors wore simple costumes, possibly from their personal wardrobes, and they hit the sweet spot of looking generally “old fashioned” without being too time specific. There was no music, except for a drumbeat that would play during some monologues of inspiration or remembrance, and the only audio effect was that of a riotous crowd.

Each member of the cast did a good job, and the five members of the African Company had a good vibe. My two favorite actors were Pierre Johnson, who played Papa Shakespeare, a character which calls for both comic eccentricity and an air of profundity despite misfortune, and Brian Webb Russell, who played the villain (a deliberately faint reflection of Richard III) with a booming, contemptuous complacency.

Some of the aspects of the plot involving romantic tension occasionally felt a little flat, but that was more due to the limitations of a staged reading as a format than it was any deficiency of acting: tension between characters is less palpable when they must frequently look down at their scripts. Director Lawrence James has expressed his wish to do a fully staged production of The African Company Presents Richard III in the future, and I can only second his wish.