Prokofiev, Shostakovich, & the Nashville Chamber Music Society at the Steinway Gallery

There’s something particularly compelling about Prokofiev’s F Minor Violin Sonata, Op. 80. It’s got this devastation and gloom about it that are impossible to miss and harder to shake. Program notes, virtually as a rule, save themselves a lot of ink by refraining from flowery, fruitless attempts to get at this aura in prose. Instead, they just quote Prokofiev himself, who apparently described at least some sections of the piece as “wind passing through a graveyard.” (If anyone out there knows the actual source for this statement, I’d love to know what it is!) But it’s not just that the sonata’s mood is so powerfully or uniquely dour—with maybe the exception of a few all-too transient moments in the energetic last movement, Prokofiev never lets up on the misery for long. It’s astounding the range of foul moods he finds across these four movements, where even a sudden (brief) turn to the tonal and tuneful in the second movement (marked eroico) feels more like seasickness than relief.

Prokofiev started work on the piece in 1938, but it didn’t see a premiere until 1946. Unlike a number of the composer’s other works, for instance his first violin concerto, which sat completed but unperformed for five years, the premiere of Opus 80 happened uncharacteristically quickly after its completion. That the piece instead remained incomplete for so many years first (and for these specific years) often adds an extra, crucial layer of mystique to the piece’s appeal. Without some clear paper trail of any number of more boring reasons for Prokofiev putting the sonata down for those years to get in the way, it’s even easier to let the relentless misery at this piece’s core truly balloon into something larger than life.

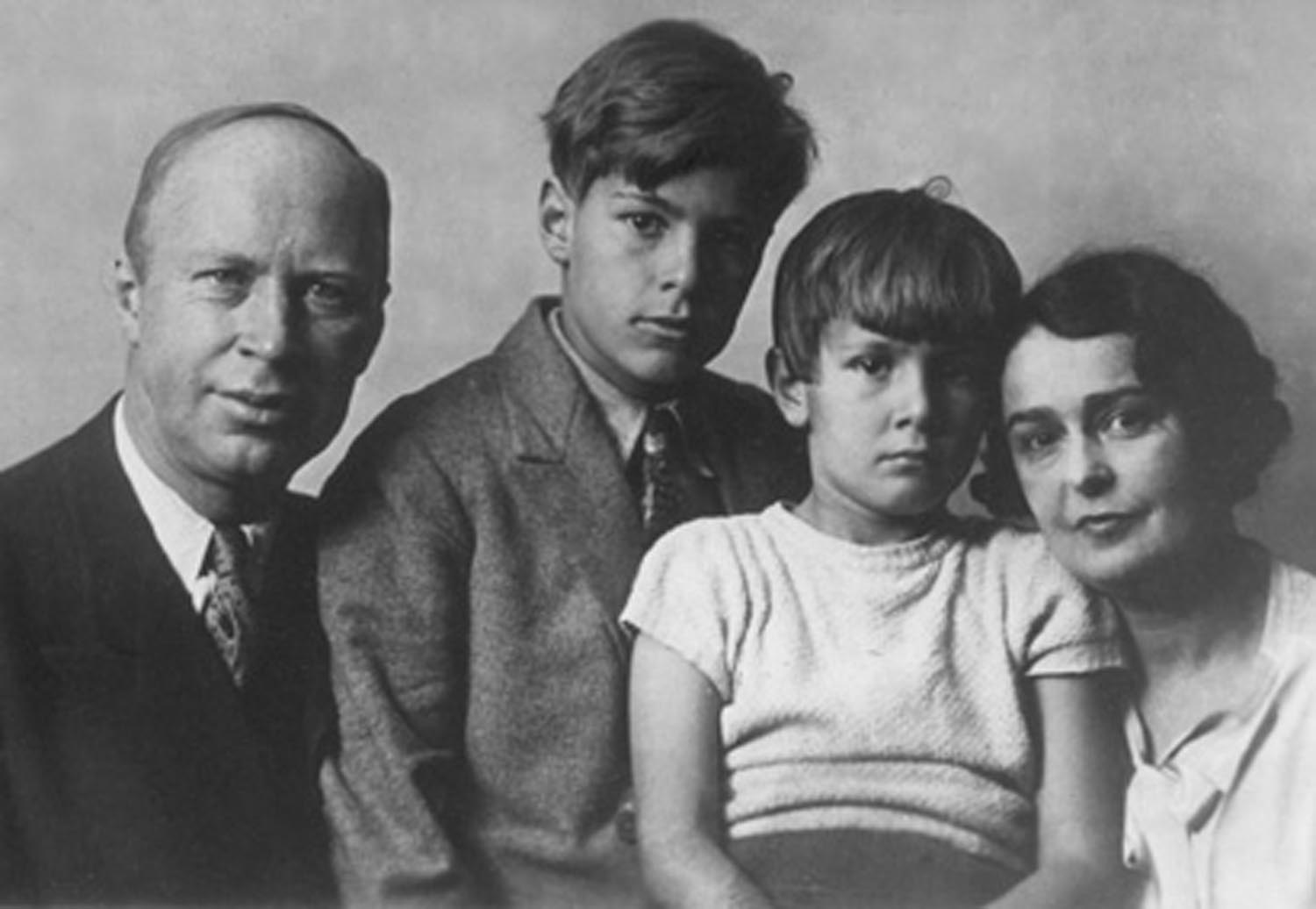

Since Prokofiev didn’t work on the piece at all during the years of the Second World War, and since it was during these years that he began to experience most directly the turbulence of Soviet political life, having moved back to the Soviet Union permanently in 1936, a political reading of the work, or at least interpreting the piece as a reflection of the dire political times themselves, is common and probably not far off the mark. Though it’s not like Prokofiev’s personal life during this same period was any less a source of misery. His marriage to the Spanish singer Lina Codina was beginning to unravel, largely as a result of the affair Prokofiev was carrying out with a woman, Mira Mendelson, who was half his age when they met in 1938. The affair carried on for years, and though Prokofiev and Lina had finally separated by 1942, they were technically married until the beginning of 1948. (Rather than being granted a divorce, their marriage was ruled invalid and therefore nullified.)

And of course, it’s not like there was ever a clear delineation between the political and personal for Prokofiev. Lina had never been a proponent of their moving to the Soviet Union, in part because of the censorship and legal troubles faced by Dmitri Shostakovich in the years just before 1936. After then having her travel visa revoked in 1938, she made several attempts to get a visa instead to leave the Soviet Union altogether, all of which were rejected. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Soviet authorities viewed Lina, a foreigner with a history of expressing political discontent, with some degree of suspicion. Very shortly after she and Prokofiev were legally separated, Lina was arrested and spent 8 years imprisoned, never seeing or speaking to her ex-husband again.

In any case, whatever the “source” of the darkness of the Violin Sonata in F Minor might have been for Prokofiev or any of his biographers, it might just as well have been the cold and gloomy rain coming down outside the Steinway Gallery last month the night of the Nashville Chamber Music Society concert. The recital hall at the back of the gallery is small but elegant, and a perfect size for their regular crowd. An intimate venue like this also helps conversations cross-populate in the audience before the performance and during the intermission, which is a special element of NCMS concerts, and one that speaks to their small-scale, personable origins as Wednesday night concerts at the Frothy Monkey.

The friendly nature and humble origins of the NCMS belie the top-notch nature of their ever-changing lineup of performers—here featuring Blair School of Music faculty members on violin and Heather Conner on piano, and the founder of NCMS MaryGrace Waggoner on cello.

The program included not just Prokofiev’s Violin Sonata in F Minor, but also his Sonata in D Major, Op. 94a, originally written as a flute sonata, but then later adapted into the Violin Sonata No. 2 (which was confusingly first performed in 1944, two years before Sonata No. 1), as well as a very early work by Shostakovich, his Piano Trio No. 1 in C Minor, Op. 8. The piano trio and Prokofiev’s Sonata in D Major were perfect foils to the F Minor sonata, especially the bubbly, up-tempo Opus 94a. The scale of the piano trio is a bit less ambitious than the violin sonatas (especially the F Minor), but it’s astounding to hear how the grand, romantic final moments squeeze out of three instruments almost an entire orchestra’s worth.

The placement of the Shostakovich second in the program, and directly after the F Minor sonata felt like a somewhat unusual choice. Not only would the shorter, and let’s say friendlier, piano trio have served as a better program opener; the vague sense of disquiet the Prokofiev leaves you with needs the kind of space a twenty-minute intermission can give. Oh well, like I said, the atmosphere at an NCMS concert is too friendly to leave everyone brooding and serious like that, and maybe it’s best not to dwell there too long after all.