From Curtis Studio

Trio Zimbalist Enters the Scene with Heft and Gravitas

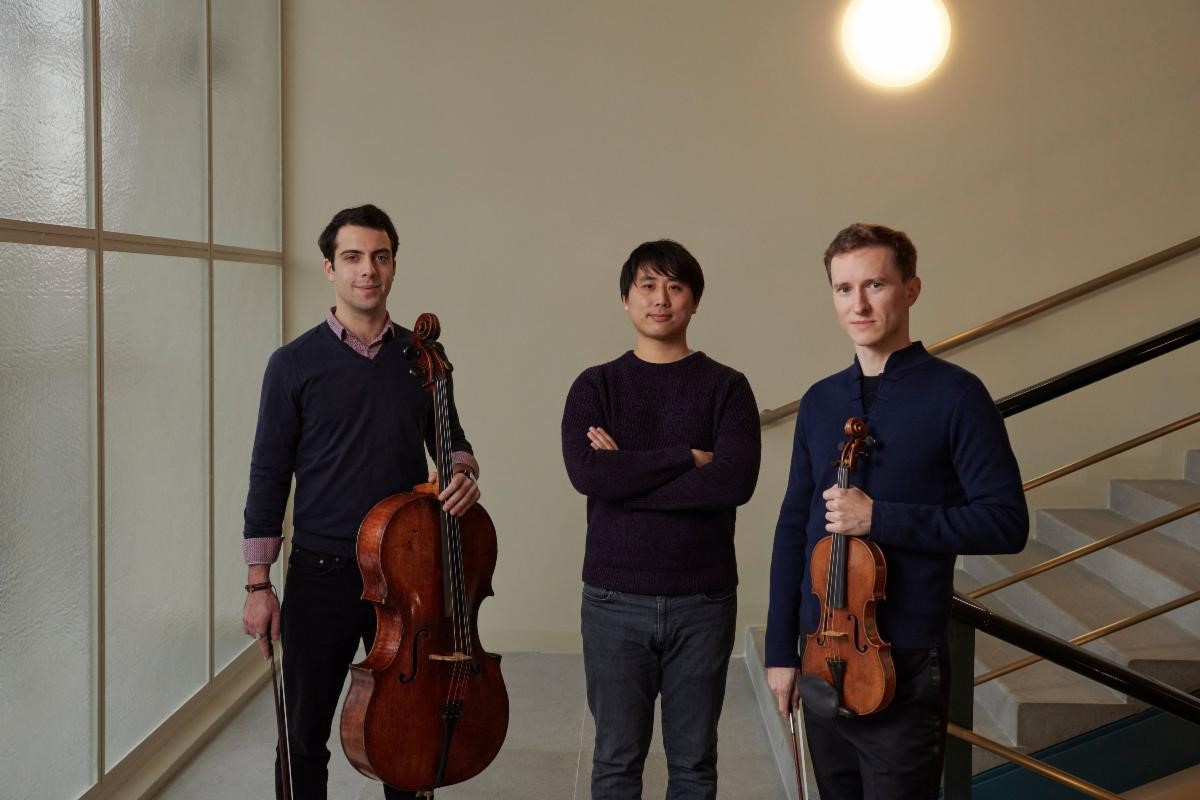

A new ensemble selecting repertoire for their debut release is an opportunity, a moment of freedom to set a tone for a group going forward. Trio Zimbalist, three Curtis alumni (Cellist Timotheos Gavriilidis-Petrin, Pianist George Xiaoyuan Fu & Violinist Josef Špaček) who have recently released their first album “Piano Trios of Weinberg, Auerbach, & Dvořák” into the wild, enter the scene with heft and gravitas. The group has thoughtfully paired three large trios that travel a chronological path, interconnected with shared geography and emotive weight.

These three trios are of Central/Eastern European composers, from the romantic era’s Czech musical pillar of Dvořák (1841 – 1904), then to Polish/Soviet/Russian Mieczysław Weinberg (1919 – 1996), and finally to living Russian-born Austrian-American composer & performer Lera Auerbach. Works were selected “in the spirit of the Dumka, containing works composed under the shadows of troubled and traumatic political histories. Dumka is a Ukrainian term meaning “thought,” and in classical music, it is a type of epic, Slavic ballad. Dumky were sung by traveling minstrels, usually Ukrainian, who played some kind of strummed instrument (e.g. the bandura, kobza, or lira). Often their songs would contain a thoughtful or melancholic lament of oppressed peoples”(Crossover Media, 2024). Considering the turmoil in the region and worldwide heightens these pieces’ already-rich pathos.

Mieczysław Weinberg’s Piano Trio, Op. 24, is a fascinating collection of contrasts to open the LP with. The first movement practically contains two movements in itself, a Prelude and an Aria. While the Prelude is strident and sustained both in its phrase lengths and heightened drama, the Aria is more questioning and brings a sense of wandering as the instruments fade in and peter out, attempting to find common melodic ground, finally uniting in pizzicato rhythm and folk sensibilities. The trio of performers tackle these vastly different soundscapes with poise – maintaining the sound and taut vibrato of the Prelude and then pivoting to the questing nature of the Aria is no simple task, physically or mentally.

The Toccata second movement continues to develop a stronger rhythmic force, with swiftly changing meters and piano chord stabs punctuating dueling strings and countermelodies. A dense and frenetic 4 minutes with nary a pause, before crashing into the third Poem movement, which is no less intense in its piano cadenza-like opening but returns to a more wandering set of ideas similar to the Aria. The Poem has more direction in its pathing, with several building moments that give way to additional plodding pizzicato, evoking a sensation of weary travelers trudging their way to some unknown journey. Finally, a Finale of some 11 minutes closes out the first selection on the album. The finale movement feels the closest to some of the other dense Romantic piano trios found on this album or traditionally in the canon as a whole, but Weinberg again diverges from the expected with a long postlude (not labeled as such in the movement, but felt) that casts aside the bombast of the opening of the Finale and instead takes nearly the entire second half of the movement to oh-so-gradually let off steam and arrive at a destination. The piano, for the first time in the work, is simplified to choral-like triads and tonality, alluding to an almost religious atmosphere for the final resting point of the journey this piece has taken.

Lera Auerbach’s Piano Trio No. 1 is a shorter, but no less impactful, middle selection of the album. Composed in the 1990s while still in her teens and twenties, Auerbach’s first foray into this ensemble configuration is confident, encompassing everything from baroque precision to modern percussive bombast. The first prelude movement is brief but contains sul ponticello moments from the very beginning, that at first listen sound like a strange choice in scratchy recording quality before revealing their deliberate juxtaposition with a sparse few clear-toned phrases. Several listens of this short movement reveal moments of contrapuntal ingenuity and an intriguing amount of cello extended techniques to flesh out the texture. The second movement begins attacca after the first, an Andante lamentoso that is achingly beautiful in its piano-led call and response moments. The movement wends its way between consonance and clash, which makes the final quiet C Major resolution that much sweeter and more hopeful.

The final Presto movement of this trio bounds through a number of ideas, including some surprisingly calm moments that evoke the opening of the work, again with appearance of sul ponticello. This tranquility is short-lived amidst the frenzied rhythmic unisons and oppositions that surround it as each instrument receives a chance to control the volume and momentum with long undulating phrases of 16th notes. The sensation of payoff is extremely satisfying upon reaching another C Major resolution before the final minute’s epilogue, although the cadence upon reaching this firmly diatonic moment is triumphant and proud in contrast to the second movement’s hushed aspiration. This 13-minute work fits in just as much of a journey as the larger works surrounding it, and is a surprisingly accessible work for an audience, despite the boundary-pushing nature of the sonic choices in composition.

Saving Dvořák’s mammoth Piano Trio No. 4 for the final piece is only appropriate, as it is subtitled “Dumky” by the composer himself, a form and label he used in several other of his compositions across his output. Due to Dvorak’s own influence, Dumky (plural of dumka) within a classical context has come to indicate “a type of instrumental music involving sudden changes from melancholy to exuberance”(Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music & Musicians, 1978). With good reason, this six-movement work is one of Dvořák’s most well-known, as the aforementioned sudden changes tug the listener’s emotions to and fro. While fundamentally rooted in Romanticism, the free form nature of this work (as Dvořák eschewed sonata form or other traditional chamber music structures in this piece) allows for a marvelous sense of a journey; rambunctious sections can be found in a Lento Maestoso movement and moments of quiet contemplation in an Allegro movement. Without diminishing the overall effect of the piece and its importance to the weighty theme of the album, the folksy frolicking moments are, frankly, a rollicking good time. Trio Zimbalist approaches these moments with gusto, hammering out the cheery sections with an energy that lets the listener picture some farm community jamboree.

Despite being a ‘mere’ three pieces, Trio Zimbalist’s debut album clocks in well over an hour. Tackling these multi-movement works with no shorter lighter pieces interspersed makes for an investment both from the performers and the listener. With impeccable preparation and dedication to the manic heights and somber lows of these works, the trio’s time and efforts are justly rewarded. This first studio outing will surely garner a core audience eagerly waiting to hear future performances and recordings as their output expands. 2024 is merely the beginning for this group, and an exhilarating beginning it is.