Mussorgsky, Corigliano and Ravel at the Schermerhorn

On January 5th, 2024, the Nashville Symphony presented Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, Maurice Ravel’s Valses Nobles et Sentimentales, and John Corigliano’s song cycle One Sweet Morning sung by Internationally acclaimed mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke.

The concert opened with Ravel’s Valses (Waltzes) which Ravel, the great assimilator, had originally written for piano in homage to Franz Schubert’s own collection of Waltzes from 1823. By 1912 he had orchestrated them for a ballet titled Adélaïde ou le language des fleurs (the ballet is rarely performed). Ravel’s incredibly rich harmonies are balanced by an equally rich orchestration and Maestro Guerrero, in his element, allowed the melodies to whirl around the room as if the Schermerhorn were some Parisian dance hall decorated with a fin de siècle decadence. The contrasting nature of the various waltzes was a lite appetizer for a much heavier meal to follow.

According to the program, and in consultation with the program, Maestro Guerrero selected Corigliano’s One Sweet Morning to record as a complement to the forthcoming recording of Corigliano’s Triathlon (performed earlier this season). One Sweet Morning was written on a commission from the New York Philharmonic to commemorate the tenth anniversary of 9/11. During its conception, Corigliano struggled with engaging the audiences memories of the event even as he sought “…both to refute and complement” them. Apparently, one of his strategies was to use poetry to ground the expression in the specific. For this he assembled bold texts from various authors. It is difficult to know the extent to which Corigliano sought to effect memories of the catastrophe, but he certainly engaged with mine.

The first movement, particularly, with its setting of Czeslaw Milosz’s text, “A Song at the End of the World,” written in Warsaw at the height of World War Two was immensely powerful. On the morning of 9/11, one of the most disturbing things about that day, was the fact that up and down the Eastern Seaboard, it was a beautiful autumn day. The disturbing thing wasn’t the sunshine, but it was the sunshine juxtaposed with the tragedy, almost as if nature had no problem with what was going on. The way that poets believe that if words don’t rhyme, they are not true, Romantics (at least since Schelling’s Naturphilosophen) believe that nature corroborates life, on 9/11 it simply didn’t. Milosz’s first strophe text carries the idea well:

On the day the world ends

A bee circles a clover,

A fisherman mends a glimmering net.

Happy porpoises jump in the sea,

By the rainspout young sparrows are playing

The disquiet portrayed by Corigliano’s his post-modern melodic line, beautifully articulated through Sasha Cooke’s elegant, radiating voice, brought this contrasting dialectic of peace and tragedy into a chilling expression. (She has a wonderful Instagram by the way). At the line “The voice of a violin lasts in the air and leads into a starry night” was played with stirring intensity as the Nashville Symphony welcomed its new concert master Peter Otto into the fold.

Personally, I found the second movement, Patroclus, more difficult than the first. Drawing its text from Homer’s Iliad, Patroclus was a violent hero and soldier who died heroically in the trojan war. The text that Corigliano excerpted for his movement graphically depicts a disturbing and remarkably violent killing spree. Corigliano’s setting is all militaristic bluster and bravado—bringing to mind President Bush with a megaphone, or Donald Rumsfeld’s WMD(s) and the decades of violence that ensued in our longest war. By relating 9/11 and the aftermath to the Iliad, Corigliano was successful in generalizing the memory and broadly contextualizing the moment into history.

The third movement is much more atmospheric and draws on a broad view of the battlefield, briefly shattered by the intimate at “My husband—my sons—you’ll find them there.” Here the balance Guerrero maintained between singer and orchestra was notably perfect. In all, the final movement brought us to a utopian dream, cadencing with Cooke representing humanity seeking, reaching, striving for an era of peace. Here at the cadence, her voice leaped beautifully across an octave and a half to a dominant harmony that left more questions than answers–as if Corigliano is admitting he has no idea what such a future would be like. Triathlon or not, I’ll be purchasing the recording of this performance when it is released.

After a nice intermission, and an all too brief glimpse of doughjoe’s work—the NSO’s new Artist-in-Residence (it was fantastic to see Ella Sheppard Moore celebrated), we headed back to our seats for Modest Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition.

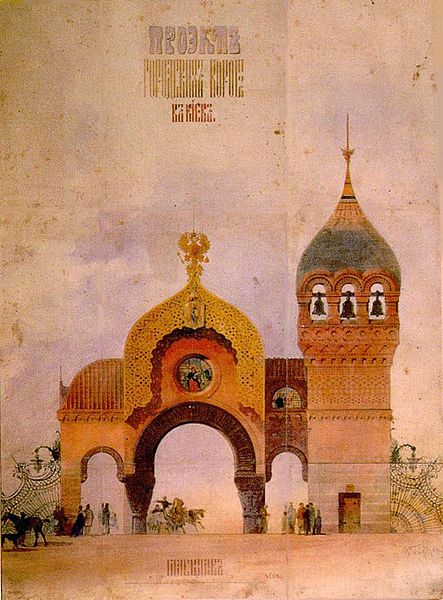

Mussorgsky’s work was written to depict the experience of visiting a memorial exhibition of Viktor Hartmann’s work not long after he had suddenly died of an aneurism in 1873. Hartmann was a friend of Mussorgsky and one of the first artists to include traditional Russian motives in his work. As such he was a hero to Mussorgsky and the other members of the “Mighty Five” who were themselves seeking to create a nationalist movement in Russian art. Interestingly, set against the previous two pieces, Mussorgsky’s work, even on piano and without Ravel’s inspired arrangement for orchestra, is clearly superior. Its starkly contrasting movements are achieved without the graphic nature of the Corigliano and they are unified by a constantly transformed “Promenade.” Indeed, Ravel’s assimilation of Mussorgsky’s style, and mimicry of that style when he orchestrated “Pictures” is more moving than anything Rimsky-Korsakov ever arranged.

The Orchestra brought Mussorgsky’s nationalism to life with a grandeur complemented by intimacy. Through Mussorgsky’s music, in Ravel’s arrangement and under Guerrera’s baton, Hartmann’s gnomes were ugly, his oxen fearful and his catacombs eerie and haunted. After Baba Yaga’s cackling, the Great Gate of Kiev arose out of the mists. It was a stirring moment and the audience was caught up in it, leaping to their feat in applause at the very end. In retrospect, it was disturbing to think that this is the same Kiev, the capital of the independent state of Ukraine, that Russia is currently invading. The stirring moment is probably akin to the nationalism that has sparked Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Mussorgsky’s is a nationalism whose design and violence caused and outlasted all the wars of the 20th century, continuing into the 21st. It begs the question: To what extent should we be performing these pieces, particularly at a time when our allies are falling in battle to this very ideal. Unfortunately, it seems that Patroclus lives on. The Nashville Symphony returns next week with Great Gershwin! A pops concert celebrating George Gershwin.