From OzArts

The truth is hidden under the posh dinner table: A review on Geoff Sobelle’s “FOOD”

Geoff Sobelle’s performance “FOOD,” brought to Nashville by OZ Arts, took me through a roller coaster of feelings and kept my head spinning long after the amusement was gone. Within 90 minutes, without an intermission, I rolled my eyes, I laughed out loud, I felt joy, pity, and sadness. I physically participated in co-making the performance and I cried…

Actor, co-director, and magician Geoff Sobelle opens “FOOD,” a performance deftly involving the audience into a participatory experience, by tricking us towards a meditation that dives into tracing the heritage of the relationship between the human and the secret ingredient which enables it to remain alive: food. We are led through the chronicle of consumption in reverse: from reminiscing about what we’ve eaten before coming to the show, all the way back to the genesis of our relationship with food: collecting, hunting, harvesting, producing, processing and mass producing.

The performance embraces and questions the power of theater to examine life through make believe. What is true on stage and what is false and how does this reflect our relationship with the reality outside of the performance space? Sobelle deceives the audience to believe the candle he lights to begin the performance ritual is fake, which one would certainly expect as a safety measure in an indoor theater setting, but is it fake really, if he blows it and the wick releases smoke?

This sets the atmosphere for the polarity of reality and fabrication, the second being one of the strongest traits of theater; its capacity to teleport the audience into a world that is not directly theirs, which through the personal experiential palette, becomes relatable. We become co-conspirators of the world we live in and are invited to share and hold responsibility for where we stand today, both environmentally and in terms of social justice. To quote playwright and screenwriter David Mamet in Theatre: “Drama … is about discovering the truth that had previously been obscured by lies, and about our persistence in accepting lies.”

We are introduced to a polished pretense dinner party around a 500-square-foot table, neatly covered by a white tablecloth and a red decorative ribbon holding the above-mentioned candle. The table is barely set with only the necessary tableware. Above the table dangles a glamorous chandelier, although when looked more closely, it is easy to notice that it’s made of cut plastic bottles and utensils, shining a reference to the debris of our consumption.

The audience is split in two: those with wrist bands that sit around the table and those behind, who witness the performance from a further distance. Thus, a division is set between those that sit at the table and those that are on the elevated seats behind them. Sobelle invites the ones on the back to help him serve wine to the ones sitting on the table. The desires of the table guests are met bluntly: when someone orders eggs, as per the text directions on the hand-written menu provided by Sobelle, they get eggs, raw, luckily unshelled. The audience behind the table observes these privileges of drinking wine and being served food, although what is served, confirmed by the comments of the relishing table ‘guests’, doesn’t necessarily sound very appetizing. The wrist-banders know how to test the quality of their wine, order their steak medium rare, pay a bill and leave a tip. The audience obeys to the choreographed ceremony and accepts this division without questioning their strata: those who pay more get first class seats. They, however, are also more exposed to the splashes of wine, the rising dust, the invitation to recite lists of food production history, share memoirs that arise from tasting the wine and certain foods, prepared vigorously and with a stinging humor.

Then there is a twist. Sobelle unapologetically collects everyone’s glasses and empties them, even the drinks the audience bought at the bar before the performance began. There is a rush to perform this act of cleaning up the table, and although he is polite, the audience becomes exposed to a forceful act that puts an end to their privileges.

After the hasty, almost caricaturized serving on roller shoes, when off duty, the polished waiter who has finished his exhaustive and sweaty shift, transforms into a gluttonous monster. His, respectively, our chafed nature is exposed. Greedy consumption of whatever comes in front of our eyes. What at first seems like a humorous interpretation of magical tricks making food and non-food disappear referentially into Sobelle’s mouth, turns into disgust. Unlike Mr. Creosote in Monty Python’s “The Meaning of Life” (1983) who underestimates his stomach and explodes, Sobelle’s character has a stomach to gobble the leftovers of his lavish guests.

The climactic turning point unfolds when Sobelle pulls the tablecloth together with the tableware, the smushed leftover food and we find ourselves in a completely different setting. The lustrous table has apparently been laid on top of barren soil. The awed audience members sitting around the table with the rising dust above them, are invited to touch the soil and trace the ancestral voyage through civilization. Herds of bison appear from under the soil, wheat grows, and a plastic plate spontaneously leans on one of the wheat stems. Sobelle’s dexterity in performing the origin of human intervention on nature in a way also hides the indiscreetness with which humanity has treated its surrounding environment. Behind and under the stage, a whole team of sound, light and trick technicians are involved in enabling the unfolding of magic. He plunges his arm through the soil to bring out the black gold that to this day is the cause of human savagery towards the land and those residing on it. As toy pumpjacks erupt, instigating the building of transportation, factories, housing, plantations, all done with the help of audience members serving little toys on food trays, Sobelle’s hands become as dirty as those of Lady Macbeth.

There’s a crucial scenography detail I’d like to end this reading with.

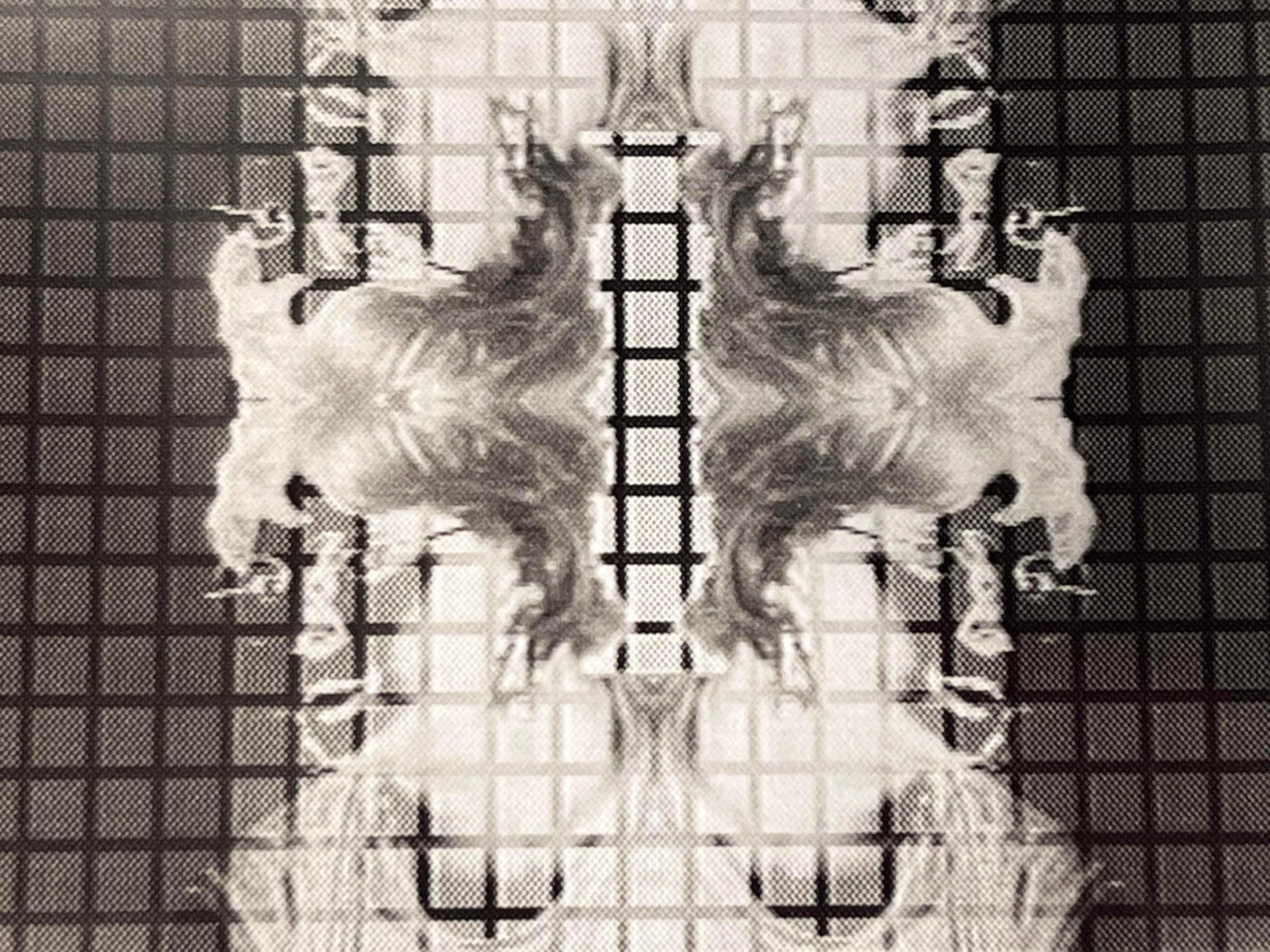

Behind the spot from where Sobelle operates as center stage, hangs a painting by the U.S. painter William Holbrook Beard named ‘Dancing Bears’(1865). William Holbrook Beard is best known for his satirical paintings of animals performing human-like activities. Sobelle’s performance slithers through satire and the absurd which makes the choice of the restaurant decor to be quite a purposeful hidden source of meaning and critique. Hanging this painting is not only an elegy to the indigenous peoples who considered animals as beings holding spiritual powers and knowledges, but it also is a dirge to those peoples whose lands were confiscated to eventually build skyscrapers on. And for what? So that in the end, we can be buried in the very same land we fought to take over.

The performance is an invitation for vigilance and acceptance of responsibility. Outside of the theater setting, will we be able to acknowledge and hold on to the connection with the rough truth that the luxurious table we eat on stands on top of a soil of rare species on the verge of extinction, evicted peoples, usurped lands, and a shattered planet, divided by the prejudice of difference? Is this the world that we want to hand to our successors?

[…] into an arena, one of the more common formats of contemporary experimental theater. Following Geoff Sobelle’s Food, this is the second time I experienced a performance at Oz Arts Nashville in this format. It is […]