From the Schermerhorn:

A Soirée between Dances and a Duel

(Versión en español aquí: https://wp.me/pabEmc-2vM)

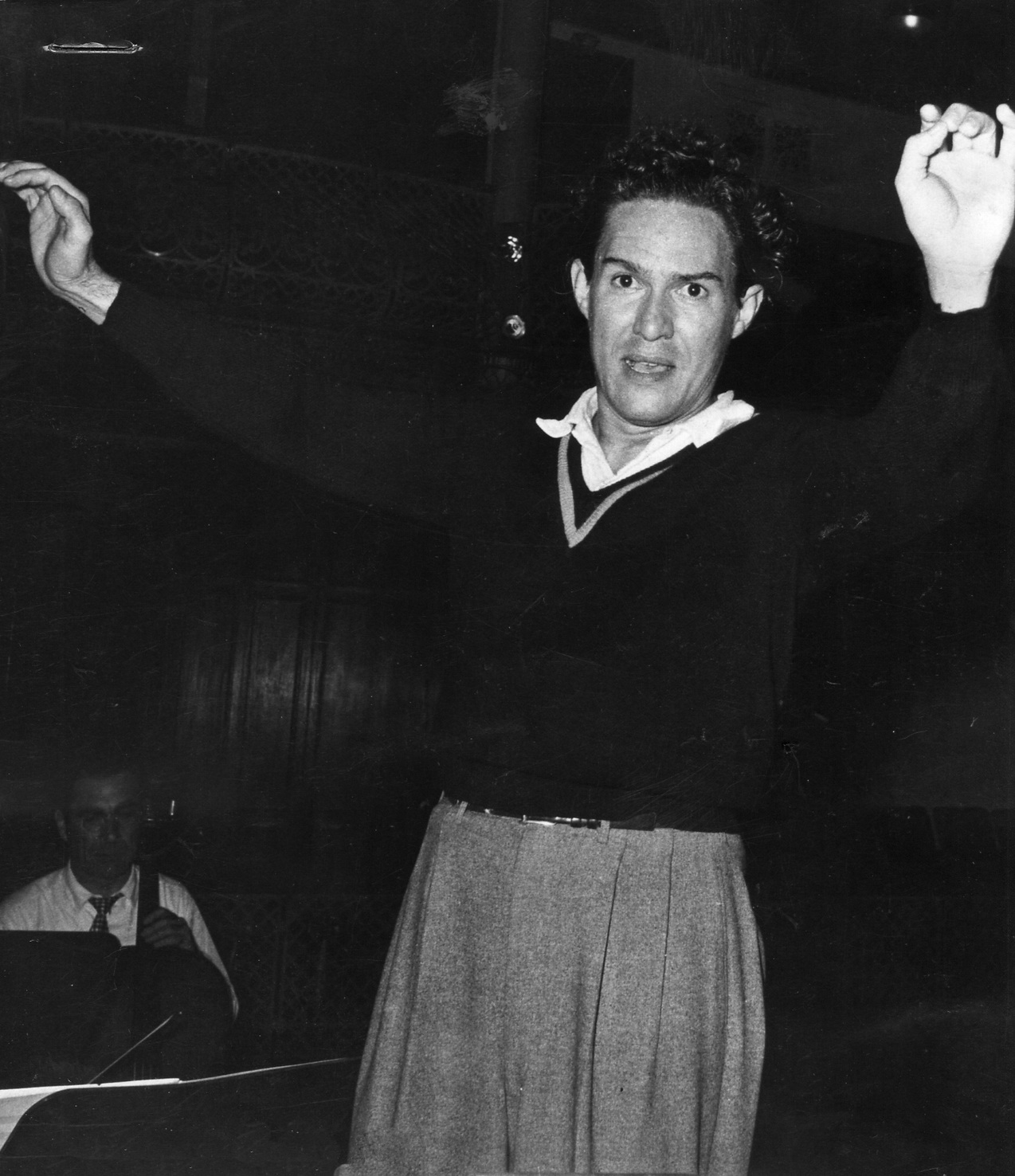

I would dare to say that the experience desired by Aaron Copland, Astor Piazzolla, and Antonio Estévez, in each composition, was revealed in a fascinating way last November 18th at the Schermerhorn Symphony Center. The Nashville Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Giancarlo Guerrero, and the Nashville Symphony Chorus conducted by Tucker Biddlecombe, expertly defined the vigorous and sensual character of Latin American folklore. The concert program combined the soundscapes of the convivial evenings of the Mexican capital in El Salón México, the porteño passages in Sinfonía Buenos Aires, and the extensive Venezuelan Savannah in Cantata Criolla.

In broad strokes, one might think that the selection of this repertoire was intended to immerse the audience in a random Latin American gala. However, these three works share hints of an era in which art claimed its autonomy, although the traditional European language remained as a means of expression. A common reference in the style of these three composers revolves around the rhythmic and motivic treatment that Igor Stravinsky employed in his compositions. Both Estévez and Copland recognized in the Russian composer the dauntlessness of overlapping tonalities and meters, as well as the inclusion of folk melodies without falling into the obviousness of variation or reharmonization. An example of this is the alternation of the metrics 2/8 – 15/16 – 17/16 in the lines of the “Devil” in the Porfía of the Cantata Criolla, while the orchestra remains in a constant pattern alluding to the corrido llanero (joropo rhythm). In El Salón México, Copland included a selection of melodies that belong to the Mexican folklore, “El Palo Verde,” “La Jesusita” and “El Mosco.”

He extracted the motifs with the greatest potential and turned them into ostinatos that he overlapped with fragments of the same melodies. The argument for this deconstruction is referenced in his words, “My purpose was not merely to quote literally, but to heighten without in any way falsifying the natural simplicity of Mexican tunes.” While there are several implicit elements of Stravinsky’s influence in Sinfonía Buenos Aires, the most evident are the accent displacements over the base rhythm of the tango, as happens in the unmistakable ostinato of the Rite of the Spring. This characteristic is ratified in the orchestration that Piazzolla used to emphasize the accentuations. The timbres of each section do not intermingle reaffirming the impact of the percussion, and the accelerated ascending motions on the piccolos alter the normal cycle in the listener’s breathing. “Maestro, I am your pupil from a distance,” Piazzolla told Stravinsky at an event where they coincided in New York. Interestingly, Estévez also longed to be a student of the Russian composer, so much so that he set out to pursue a scholarship that would allow him to continue his studies at Columbia University where he was a professor. Although he achieved his goal, Stravinsky moved to Los Angeles when Estevez arrived in New York.

Another common factor in this repertoire is the nationalist exploration of each piece. All three composers undertook a trip to the region that would serve as their inspiration. Copland wrote El Salón México from his perspective as a tourist at a dance venue in the Mexican capital. This was the place where the “danzoneros and rumberas” (dancers) gathered and would not let the night die on their dance floors. Estévez met Florentino and the Devil in the defiant verses of a Venezuelan poem, motivating him to pack his bags to venture into the traditional towns of Venezuela’s llanera music. After a New York childhood, Piazzolla settled in Buenos Aires intending to become an authentic tango performer. In his alternation as a bandoneon player and composition student of Alberto Ginastera, Piazzolla had the revelation of printing the timbre of this instrument in an unprecedented orchestral amalgam for his Sinfonía Buenos Aires. It is incredible how despite the rhythmic and harmonic complexity in the structure of each work, the labyrinth of emotional states, anecdotes, and climates, the music flows and does not alter its essence. The singularities of Banda music, tango, and joropo are latent from beginning to end in a discourse that is at times suggestive and at other times concise. Each element is disposed of as if it were an impressionist painting where the scene makes sense when is observed as a whole.

In a similar effort to that of Aaron Copland as a cultural diplomat in the search for Latin American gems, conductor Giancarlo Guerrero managed to bring together on the same stage world-renowned artists who are specialists in the repertoire that would be performed. Argentine bandoneonist Daniel Binelli, who was part of the New Tango Sextet led by Astor Piazzolla, displayed his virtuosity in performing the written parts of the two bandoneons required in Sinfonía Buenos Aires. Venezuelan singers Aquiles Machado (tenor) and Juan Tomás Martínez (baritone), have participated in numerous Cantata Criolla stagings. Their symbiosis with this musical work is evident; the written vocal lines urge a lyrical style impregnated with llanera cadences; a task completely achieved by the two artists. The search for gems does not end here, there is an element of inestimable value in the orchestration of this cantata, the maracas llaneras. This instrument of simple appearance reserves the best secrets in terms of execution. Its school is the Llano itself. For this reason, the percussion section required an additional member to play this line; it was essential to find a performer from the Venezuelan plains. Alcides Rodríguez, clarinetist of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra, was in charge of giving life to this authentic joropo shaker.

Certainly, this is a magnificent cast for a splendid repertoire. Those of us who attended the mind-blowing pre-concert talk given by conductor Giancarlo Guerrero got a first-hand account of the occurrences surrounding the concert. However, given its importance to the event, it was imperative that this information also be highlighted in the distributed program. It is understandable that the bandoneon on this occasion was not a soloist, but its involvement on a foreign stage and naturally due to the celebrity of the performer, deserved to stand out in the orchestra setting. Logistical shortcomings hindered the interaction of the audience with maestro Daniel Binelli, as well as the final recognition for his masterful performance.