From Nashville Opera

Pagliacci’s Suffering and Guilt

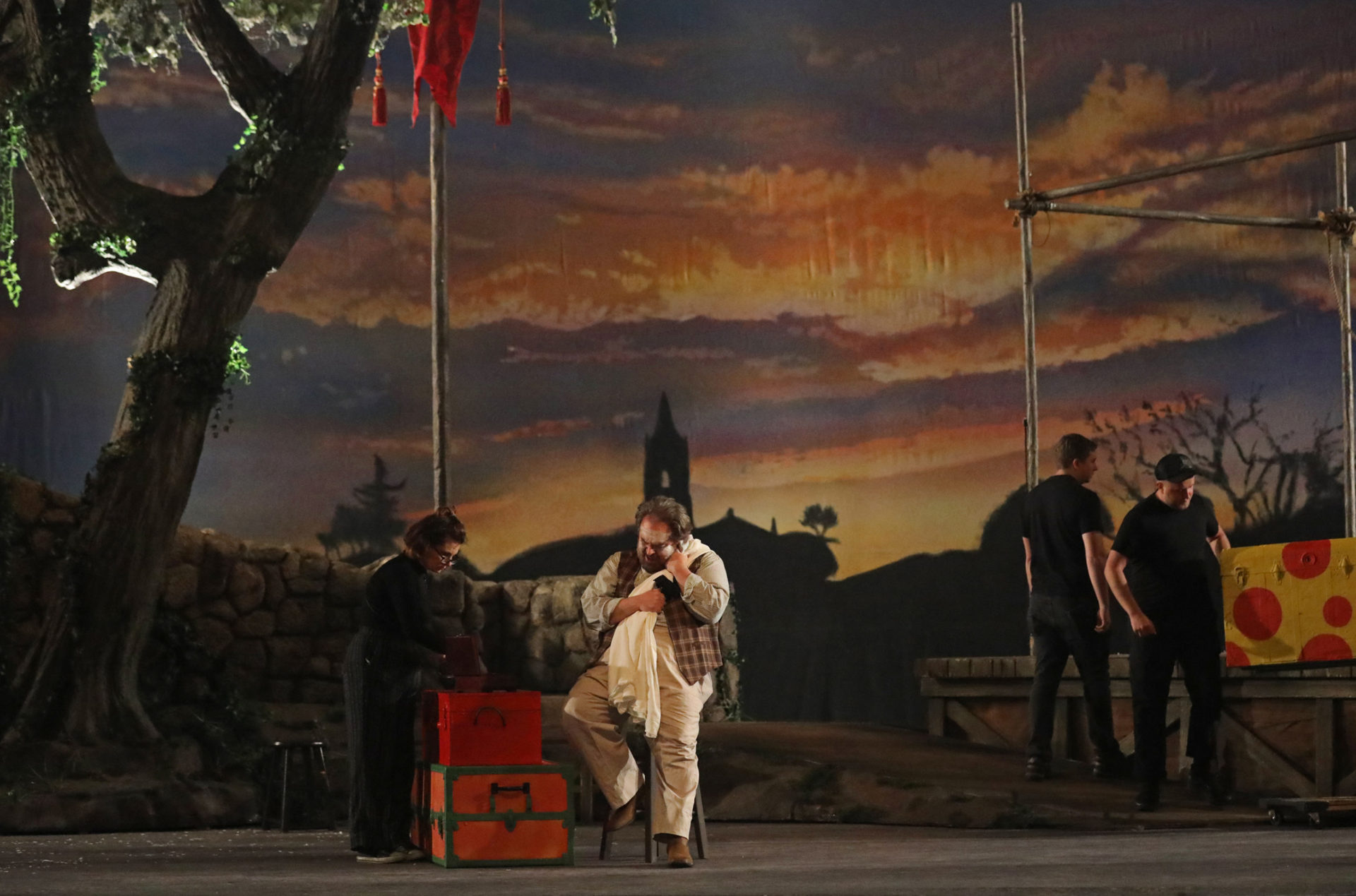

On September 21 Nashville Opera presented a wonderful performance of Ruggero Leoncavallo’s verismo masterpiece Pagliacci at Jackson Hall in the Tennessee Performing Arts Center. A reprise of the company’s staging from a decade ago, the performance and production were as fresh as ever and a delightful way to start the new season.

H. Auden once wrote of Pagliacci: “No dramatist ever believed in real life that the poor did not suffer, but, if the dramatic function of suffering is to indicate moral guilt, then the relatively innocent cannot be shown to be suffering.” Here, I think Auden is close to the point of verismo opera, directing us to the relationship between a character’s guilt and suffering, however, he seems to miss the aspect that makes these works so powerful. The suffering humanizes each character and mitigates or at least balances their moral guilt; it is what makes these works so darkly tragic and heartbreaking. This is the measure of a good production of verismo opera, not through the recognition of each character as “antagonist” or “protagonist” but an understanding of each character’s actions as explained by their suffering.

Take, for example, Canio, the central character with practically zero agency, and played wonderfully by tenor Jonathan Burton. Canio is depicted at the outset as a loving but jealous man who rescued Nedda from the gutter. His horrid, murderous crimes at the end are a result, not just of his own jealousy, but of the machinations of the monstrous Tonio. The central aria, the most beautiful moment, perhaps in all of verismo opera, is his aria to end the first act, “Vesti la giubba.” A man, dignity destroyed, honor lost, is forced to play the clown: “Laugh, Pagliaccio, your love is broken, Laugh of the pain, that poisons your heart.”

The challenge of the aria is, I think, in the delivery. It sets fairly well within a tenor’s range and a singer might be tempted to take it through its paces belting the highest notes, but the character is singing through tears as he watches his happiness and sanity flee. The notes need to be hit clearly and brassy, but with a gentle delicacy that Richard Wagner never understood about Italian opera, a nuance that Caruso found over 100 years ago. On Saturday, Burton was right there. Perfect intonation and a gentle vibrato that expanded as the emotions kicked in, and dropping the power as his character’s dreams were dashed and he succumbed to his fate. It was a characteristic stroke of genius for Director Hoomes to leave Burton onstage, weeping, and in character without curtain as the lights went up and intermission began. The audience was transfixed in their applause.

Suffering from her own binary of guilt and suffering, Keri Alkema as Nedda was beautiful. Alkema made serious waves as Tosca before the pandemic; another tragic heroine, and here she has found another excellent vehicle for her acting and singing talents. When she rips into the monstrous Tonio at the beginning, it is authentic enough that you feel for him (she is the cause of his suffering). The timbre of her instrument was well controlled, leavening Nedda’s anguish with a hope that lasted until the final moments of her character’s life—a gentle nuance let the audience know that when she sang “A stanotte, e per sempre io sarò tua”(until tonight, and I shall be yours forever) to Beppe as Arlecchino, she was really singing to Silvio-rendering the ingenious blocking of Silvio and Beppe almost obvious.

Overall, Pam Lisenby’s costume design was wonderful, but perhaps Nedda’s onstage costume and makeup were too much Raggedy Ann and not enough Columbina? Silvio’s polo was also a bit anachronistic but it did make him stand apart from the rest of the cast. Speaking of anachronisms, and you can call me a hypocrite, because it was delightfully fun to see Silvio’s lute done up as Eddie Van Halen’s Frankenstrat.

From the perspective of acting, Andrew Manea’s Tonio stole the show. His voice was in fine form, and his matter-of-fact presence at the prologue was perfect, while his character’s arch of sympathetic-until-rapey progression in the first act cinched the tragedy. The production was wise to break with custom and assign Tonio the final line, the sneering “La Commedia è finite!” The decision makes Tonio a really evil puppet master, and with an actor like Manea, who could resist?

Joseph Lim’s Silvio, came off well as an innocent victim, although I do wonder if audiences in the past haven’t seen him as an antagonist for his role as the other man. Anthony Ciaramitaro’s Beppe was excellent too, with a strikingly beautiful, shiny tenor. Dean Williamson’s orchestra and Stephen Carey’s chorus performed with the brilliance that has come to be the expectation in Nashville. Finally, JaVonte’ Marquez and Joi Ware’s dances, at several points, provided an excellent levity that gave bright, joyous contrast to this heart-breaking tragedy—it was a wonderful night! Nashville Opera returns in November with The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat.