The Nashville Symphony plays Copland, Slatkin, Elgar

A Celebration, An Elegy, A Majestic Ending

Fresh from their triumph in the world premiere of The Jonah People, an opera the symphony commissioned from composer Hannibal Lokumbé, the Nashville Symphony presented a solid program of more traditional works on Saturday night May 6 in Schermerhorn Symphony Center. These works, with famed American conductor Leonard Slatkin at the helm, showcased Nashville’s strengths, the lush string section with fine work by the brass section.

Copland’s orchestral suite from his ballet, Rodeo, is always a crowd favorite, a well-deserved tribute to an exciting piece of music. From the bold, dynamic “Buckaroo” to the delicate vulnerability of the “Corral Nocturne; from the sometimes raucous, sometimes sensual “Ranch House” to the “Saturday Night Waltz” redolent of the rich calm of hard-working ranchers enjoying a welcome break; ending with the famed “Hoedown,” this work sings of America. Its diverse musical styles celebrate a diverse country with hope for the future.

It’s ironic that Aaron Copland, a New Yorker born in 1900 who rarely left the northeast, was fascinated by the rest of this great land. Somehow the American Dream was the focus of his fantasies, resulting in works set in Appalachia (Appalachian Spring), on the border of Texas and Mexico (Billy the Kid), in his native New York (Quiet City), and pieces encompassing the breadth of the entire country from sea to shining sea (Fanfare for the Common Man). Rodeo is perhaps the most attractive distillation of the breadth of Copland’s skill: beauty, wonder, and raucous independence.

Slatkin conducted with efficient gestures that had the orchestra turning on a dime effortlessly, only bearing down in spots like the descending cello scales in “Hoedown,” the fierce down bows complemented by a percussionist gesturing the beats before striking the cymbal. The joyous chaos of this piece had the audience on their feet by the last note. Nobody had to ask “Where’s the beef?” It was a meaty performance, properly seasoned.

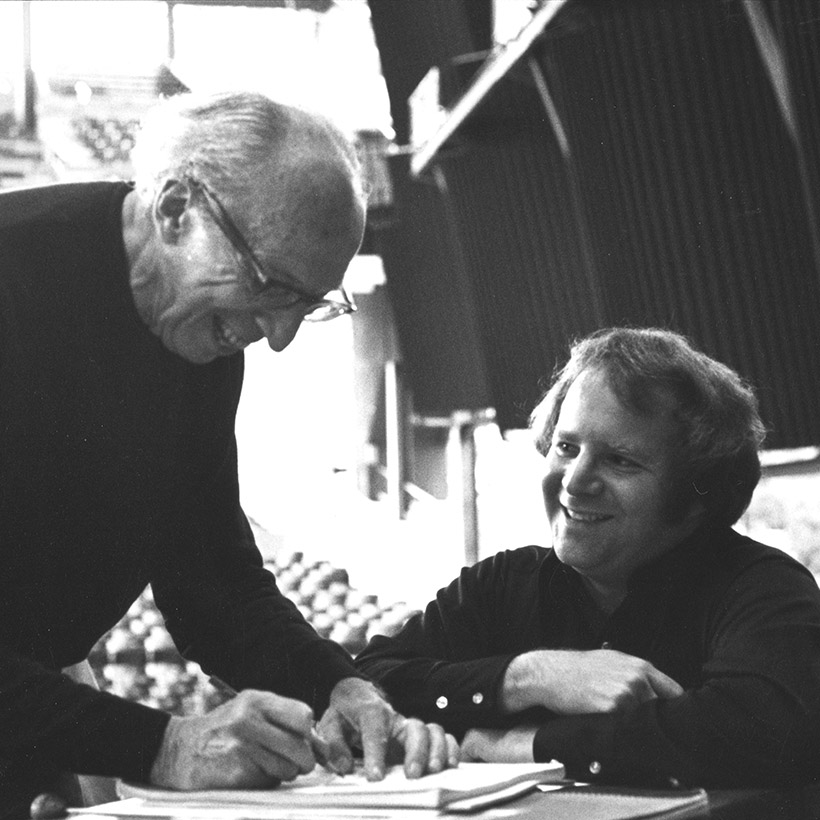

A perfect next stage was Slatkin’s own composition, Kinah. Written as an elegy for his parents, this work scored for strings, percussion and brass stood on its own, but the backstory was quite moving. Slatkin’s parents were both skilled musicians for the movie studio orchestras of the Forties. As premier violinists and cellists of their time, they were in preparation for their lifelong dream of performing Brahms’ Double Concerto together. The night before the performance, tragedy struck, Slatkin’s father died suddenly.

As a result of this dream forever deferred, Slatkin has ethereal themes from the Brahms’ slow movement started by an offstage violinist and cellist—themes started, but never completed. An offstage flugelhorn, played with gorgeous tone by principal trumpeter, William Leathers, seems to play the role of the trumpet in Charles Ives’ Unanswered Question, an omniscient narrator whose winding melody outlines the shape of a question mark, perhaps asking how this could happen, or perhaps accepting fate’s inevitability. It was a touching tribute to Slatkin’s parents and the audience responded with great appreciation for the music and its meaning.

The second half of the program moved across the sea to Edward Elgar, a composer as English as Copland is American. The link to Brahms revealed a connection from Kinah to Elgar’s first symphony. Like Brahms, Elgar was a major composer of his era who was late to writing symphonies, a composer whose first symphony was eagerly awaited and accepted by music lovers. While Brahms felt the weight of Beethoven looking over his shoulder, Elgar felt the shadow of Brahms hovering over his music desk. And like Brahms, Elgar stuck to the traditions of symphonic music in four movements, rejecting program music (music based on an artistic or literary theme).

Elgar, known best for “Pomp and Circumstance” and the “Enigma Variations,” intended the first movement—sonata-allegro form with a slow introduction—to be a noble statement, a slow English call, intended for “persuasion, not coercion.” There were some pitch problems between the clarinets and violas in the midst of the composer’s rich warm harmonies, but the clarinets reclaimed their time with a lovely diminuendo at movement’s end.

The allegro molto second movement referred a bit to Mendelssohnian scherzos and, once again, regal British marches. The trio had a touch of the pastoral elements of Brahms. There were, in fact, touches of Brahms throughout—hemiolas in the first movement, syncopation in the last, lush strings throughout with woodwinds in octaves above them. While this massive work was well-played and well-received, it paled (slightly) in comparison to the innovations of the first half, though that might be my bias in favor of the vigor of American music.

Regardless, this was a very fine program of very fine music, played very well. Slatkin brought the best out of the orchestra. This performance deserved a much bigger audience than two-thirds of a hall, but the audience clapped with great enthusiasm, each piece receiving a well-deserved standing ovation.

And speaking of Brahms, Symphony musicians will play his magnificent clarinet quintet (clarinet plus string quartet) Tuesday, May 16, 2023, at 6 pm, followed by a program called “Virtuoso Fireworks” with Giancarlo Guerrero, conductor and guest artist, Bomsori Kim on violin. This set of three performances will be held at Schermerhorn on May 18 (7 pm), 19 (8 pm), 20 (8 pm).