Just in from Cleveland:

Welser-Möst Conducts Schubert – An Innovative Program by The Cleveland Orchestra

in·no·va·tion

/ˌinəˈvāSH(ə)n/

the action or process of innovating

“Innovation is crucial to the continuing success of any organization.”

Classical music organizations have received criticism for mostly presenting performances of pieces that have already become well-established in the canon of repertoire. Challenges have been made for such organizations to innovate. Calls demand for the curation of more diversified perspectives and experiences, including the championing for and commissioning of, new works that strive to receive more play than merely a premiere. It seems that The Cleveland Orchestra has responded to this charge – both with respect to programming, as well as the ways in which the institution connects with audiences.

Programming Innovations

During the winter and spring portions of The Cleveland Orchestra’s 2022-2023 season, perennial favorites are accompanied by various other works which are still establishing themselves within the regular cycle of repertoire. Sustain (2018) by Andrew Norman, Unsuk Chin’s SPIRA – Concerto for Orchestra (2019), and the world premiere of Wynton Marsalis’ new trumpet concerto written for principal trumpet, Michael Sachs, are examples that speak to this intention. Equally encouraging is the way in which established repertoire is paired and presented in a recent series of performances titled ‘Welser-Möst Conducts Schubert.’

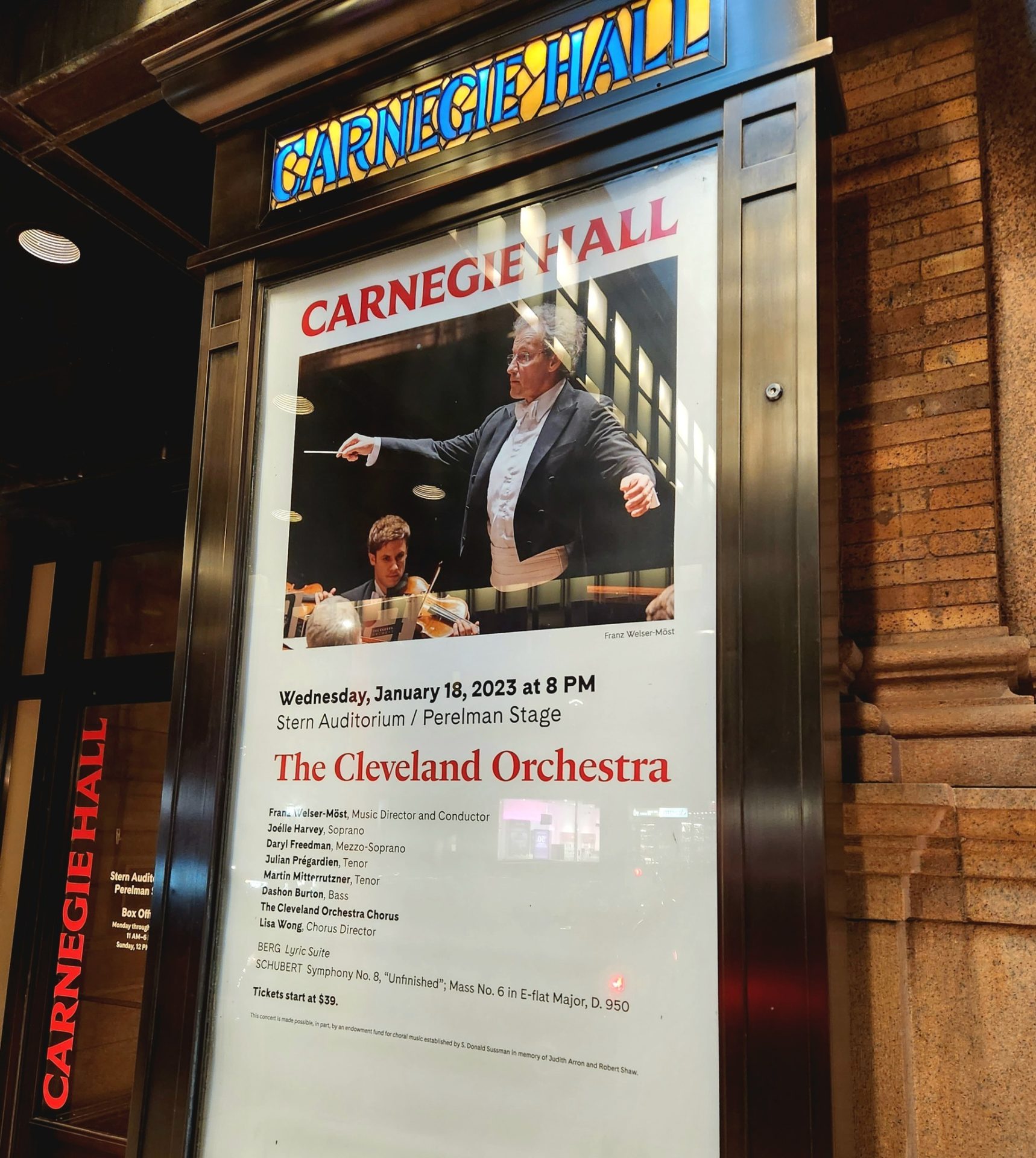

Three performances of ‘Welser-Möst Conducts Schubert’ were offered for audiences in the Jack, Joseph, and Morton Mandel Concert Hall at Severance Music Center in Cleveland, Ohio, before the program traveled to New York City’s Carnegie Hall for one sold-out performance the following week.

The 1928 version for string orchestra of Alban Berg’s Three Pieces from Lyric Suite were combined with the two movements of Symphony No. 8 – “Unfinished” in B minor, D. 759 by Franz Schubert. The composite was offered in the following order and presented without applause between movements:

Alban Berg, “Andante amoroso” from Three Pieces from Lyric Suite

Franz Schubert, “Allegro moderato” from Symphony No. 8 – “Unfinished” in B minor, D. 759

Alban Berg, “Allegro misterioso – Trio estatico” from Three Pieces from Lyric Suite

Franz Schubert, “Andante con moto” from Symphony No. 8 – “Unfinished” in B minor, D. 759

Alban Berg, “Adagio appassionato” from Three Pieces from Lyric Suite

Breaks between selections were brief, only allowing a moment of silence before the next sonic landscape was offered. The first half of the program lasted roughly forty minutes. Late seating could only occur during intermission because of this reality.

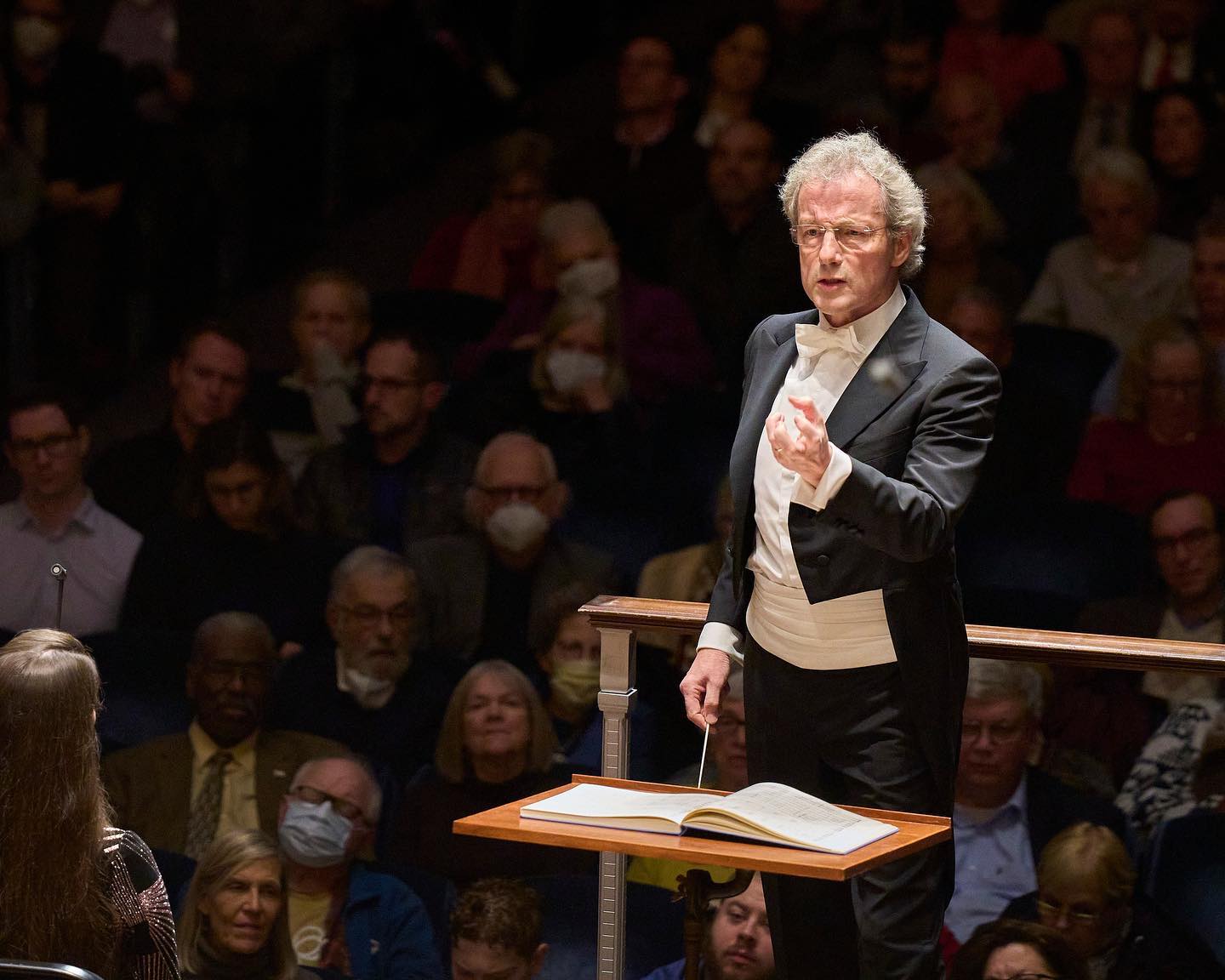

Music Director Franz Welser-Möst offers that, “Alban Berg . . . is sort of the musical grandson of Franz Schubert. When you play them back-to-back, you can hear that they’re related – that what Schubert didn’t, or couldn’t, finish, Berg carried forward. It’s always rewarding to show where something comes from, where something goes to, and that music of different times is connected.”

Uniting ‘grandfather composer’ with his ‘grandson’ creates a listening environment that spans just over a century. While threads of similarities can be drawn between the writing of Berg and Schubert, it does require a larger-than-usual effort from the listener to absorb this cross-generational offering in real time.

Credit must be given to both players and conductor for executing Alban Berg’s “Andante amoroso” in such a manner that allowed for the movement to brilliantly evaporate into a moment of silence; a silence that was rather quickly proceded by the hauntingly beautiful melodic opening gestures of Franz Schubert’s “Allegro moderato” movement. Similar success was found in the transition between Schubert’s “Andante con moto” movement to the “Adagio appassionato” of Berg. While various bowing techniques, the density of gestures, and interplay between sections does have a scherzo-like quality, Alban Berg’s middle movement, “Allegro misterioso – Trio estatico,” left this listener feeling as though the evening’s repertoire experiment had inconclusive results. Perhaps additional listening and more score study could better prepare one for such an auditory amuse-bouche that shifts compositional styles.

After intermission the program concluded with Mass No. 6 in E-flat major, D. 950. Written in the last year of Schubert’s life, the premiere performance of this fifty-minute work was conducted by the composer’s brother just four months after Schubert had passed. Because of this, Welser-Möst speculates that perhaps there are elements of a requiem laced throughout the piece. Maestro Welser-Möst also offers in his program note for the work that Franz Schubert created a Mass form that was more pedestrian than a number of other composers: “Rather than express subservience to God, this music focuses on individual devotion, human emotion, and our own relationship with the divine.”

Lisa Wong, Director of Choruses, seems to have prepared The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus rather meticulously for this series of performances. While there were discrepancies with respect to the vertical alignment for a few consonants, the aesthetic achieved by this volunteer body was often mesmerizing and well-balanced throughout voice parts. Logistically, all members of The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus wore masks for the entirety of the performance. There were two specific instances in which Franz Welser-Möst demanded an immediate change in balance between vocal forces and instrumental contributions – the first in which woodwind soloists were encouraged to create sonic real estate and the latter in which the string consort was hushed from otherwise fully committing to the dynamic insinuations of the song-like topography. It is unclear whether this restraint in volume was the resultant of the masks creating an imbalance amongst forces or whether these requests from the podium were artistic decisions that intensified the music’s emotional output.

The “Credo” welcomed the first opportunity in which the program’s vocal soloists were featured. Tenor I, Julian Prégardien, and Tenor II, Martin Mitterrutzner, appeared to effortlessly match in tone and character of vibrato, working in tandem to maintain an ideal balance that, not so dissimilar to a kaleidoscope, created opportunities for each artist’s offering to shine in a coordinated effort. The penultimate movement –“Benedictus” – finally brings the composition to the vocal solo quartet. While the writing and the way in which it was performed was worth the wait, Schubert disappointingly composed with an economy that leaves one wanting more moments with the vocal quartet. Bravi tutti – Joélle Harvey, soprano; Daryl Freedman, mezzo-soprano; Julian Prégardien, tenor; Martin Mitterrutzner, tenor; Dashon Burton, bass-baritone.

Aside from the scandalous hidden messages that were composed into Three Pieces from Lyric Suite, mentioning nothing about the marital affairs that served as the impetus to do so, Alban Berg remains modern sounding even almost a century after having been written, suggest Hugh Macdonald and Eric Sellen, program note contributors for The Cleveland Orchestra. Because of this, an opportunity was missed to close the program with a current work, the vernacular of today, that would have allowed this program’s dialogue to traverse from the First Industrial Revolution with Schubert, to Post-World War I society and Berg, to a commentary about the twenty-first century. Perhaps future seasons might offer such a thought-provoking experience.

Organizational Innovations

Subsequent to live, in-person performances, The Cleveland Orchestra has developed initiatives to meet audiences through various digital media platforms. These innovations seem to provide more autonomy and speak to ways in which society currently consumes information and entertainment.

In October 2020, The Cleveland Orchestra began streaming performances, interviews, and behind-the-scenes content with the initiative, ‘In Focus’ on Adella Premium: https://www.clevelandorchestra.com/attend/seasons-and-series/in-focus/. The concert reviewed here was being recorded for a future release on this very platform. Memberships currently cost $14.99/month or $119.99/year.

‘On a Personal Note’ is a podcast that connects audiences with orchestra members, conductors, those with special affiliations to The Cleveland Orchestra, and guest artists: https://www.clevelandorchestra.com/podcast. Music Director Franz Welser-Möst speaks to his life-long relationship with the music of Franz Schubert on a recent episode. From childhood memories of his mother playing piano to a near life-threatening car accident while in college, Welser-Möst’s vulnerability informs one about his perspective – perhaps even providing a possible explanation for the two aforementioned instances in which Welser-Möst committed to moments of stillness and intimacy through dynamics in Schubert’s Mass.

Lastly, The Cleveland Orchestra has founded its own recording label. While not particularly innovative as a form of media, this reality is innovative from the vantage point of business savviness. No longer do arts administers need to succumb to the pressures of record executives and the legalities of contract language. Presumably now, The Cleveland Orchestra is free to record the repertoire it desires when deemed convenient for the organization. Let us hope that releases will also share in this spirit of continued innovation.