Theatre Nohgaku at the Frist

It was a misty gray afternoon, not cold, but comforting, a stay-inside kind of day, the kind of day you commonly see in the Japanese countryside, the kind of day you commonly see from the windows of the lightning-fast shinkansen train headed from Tokyo to Kyoto. It was the kind of day when you hope the mist will clear away just long enough to see the celestial peaks of Mt. Fuji in the distance.

Nashville’s Frist Museum, quiet on Sunday afternoon December 4, 2022, provided the perfect setting for one of the oldest, most serene, continuing art forms in the history of theater. Theatre Nohgaku, an international ensemble, honorably preserves this masked art form, Japanese Nōh drama, whose words, movements, music, costumes, and dance represent 600 years of history.

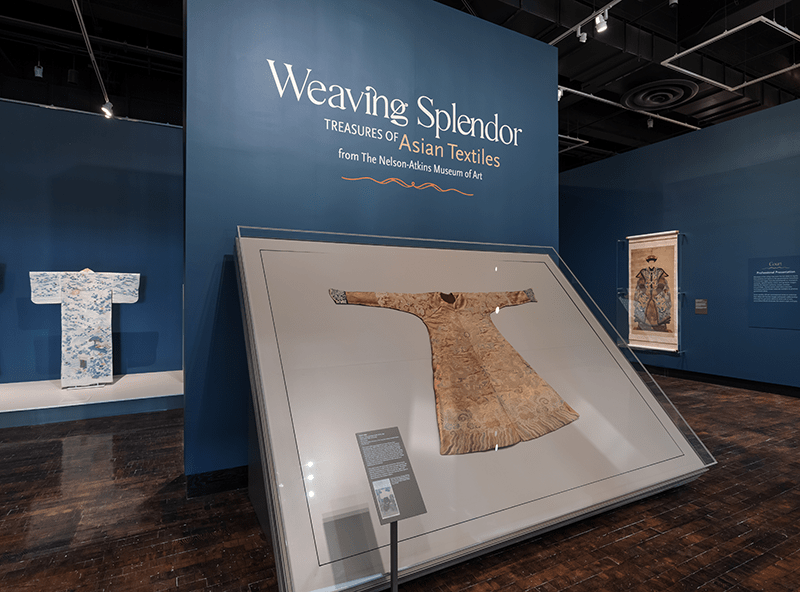

As a complement to “Weaving Splendor: Treasures of Asian Textiles from The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art,”, an exhibit on Asian weaving techniques, the Interpretation Division, directed by Meagan Rust, hosted Theatre Nohgaku’s concise lecture demonstration on Nōh techniques. Because of the skeleton crew of only three performers for excerpts that would normally require at least a dozen, the performance was just a barebones synopsis. Despite these incomplete aspects and a few stylistic issues, the performance was remarkably effective and well-received by the diverse audience. Members of the ensemble presented excerpts from four famed Nōh plays, each preceded by a demonstration of specific aspects of Nōh performance, including techniques for singing, movement, and instruments.

(Those unfamiliar with Nōh drama may want to read my primer)

Story synopsis:

The spirit of Lady Izutsu, comes to a traveling monk in a dream. In this excerpt, she still seeks her unfaithful husband in the afterlife, dressing in his cap and robes while dancing as she once did.

The “Jewel Song [Tama no dan]” from Ama, is a tragic tale of a working-class mother who sacrifices her life in order to gain social status for her son.

Sumidagawa displays a mother who has finally located her kidnapped child, only to find he has died. This realization, coming from the boatman as they cross the Sumidagawa River, leads to her sobbing at her son’s gravesite.

In Hagoromo, a fisherman chances upon a gorgeous feather robe hung on the branches of a pine tree. He agrees to return it to the spirit who needs it to return to the heavens, if she will dance for him.

David Crandall, a founding member, introduced the vocal techniques of kotoba and yowagin. Used for dialogue or monologue kotoba consists of deep-pitched chanting with wide, slow vibrato. Yowagin, more melodic, stays mostly in the midrange with long tones topped off by lighter, tighter vibrato. Crandall, a Michigan native with degrees in Japanese literature and music, sang a kotoba style excerpt from Itsuzu in Japanese and denonstrated yowagin in English for “The Jewel Song” from Ama. Both styles were clearly evident in the English rendition of dialogue and arias from Sumidagawa.

Even in English, the excellence of the kotoba chanting style of vocal timbre and vibrato was an unexpected success. Crandall’s training in literary translation and deep understanding of traditional Nōh vocal performance based on more than twenty years study resulted in wonderfully effective adaptations of the texts. In fact, his technique was so authentic, I could close my eyes, imagining myself back in Tokyo.

Jubilith Moore demonstrated the suriashi, the standard slow gliding steps of Nōh, along with other movements like shiori, moving one or both hands down in front of the mask to represent falling tears. She and Crandall also explained the complex construction of masks made to last for generations.

Musicologist David Salfen, Professor of Music at University of the Incarnate Word in San Antonio introduced three of the four standard instruments for the hayashi ensemble that accompanies Nōh singing and dance, but also provides palette cleansers like “Chu-no-mai.” Salfen played the Nōhkan, a high-pitched wooden transverse flute which, uniquely, is a melodic instrument serving a rhythmic function. Moore played one of the two hourglass-shaped tsuzumi drums, each carved from a single piece of wood. Both have heads of horsehide on each end bound with heavy hemp cords.

Like the tama talking drums of West Africa, Moore’s ko-tsuzumi shoulder drum has pitch changes caused by squeezing and releasing the cords as the head is struck by the right hand. Crandall’s larger o-tsuzumi hip drum is designated as “male” but is higher-pitched because it is struck by hardened papier mâché thimbles. The fourth drum, struck with sturdy dowels only appeared in the final number, the iconic “Feather Robe Dance” from Hagoromo. One missing aspect of the instrumental explanation was the amazing kakegoe. These loud drum calls, signaling section breaks and tempo changes, continue throughout the performance regardless of whether singing or dancing are present.

This unusual trait was later addressed during the brief Q/A after the performance, but for those new to Nōh, an earlier mention would have served well. Another aspect diverging from my past Nōh experience is the sense that the performance was too fast, that the company had adapted the tempo for American audiences. This was a disappointment because exhibiting tremendous control through glacial slowness is one of Nōh’s most unique characteristics. The highly stylized gestures typically used by the hayashi instrumentalists for each drum stroke or removal of the flute from the lips also seemed a bit in absentia.

Overall, however, the final Hagoromo excerpt, the dance a heavenly spirit offers to a lowly fisherman in exchange for the return of her feather robe, combined all the main elements the audience had viewed so far: vocal techniques, dance, instruments, bringing a fascinating program to satisfying completion. Theatre Nohgaku was a welcome peak in Nashville’s artistic landscape on this cloudy day, a glimpse of Mt. Fuji.