The Nashville Symphony plays Coleridge-Taylor, Debussy, and Mendelssohn

Nature’s Passion on Land and Sea

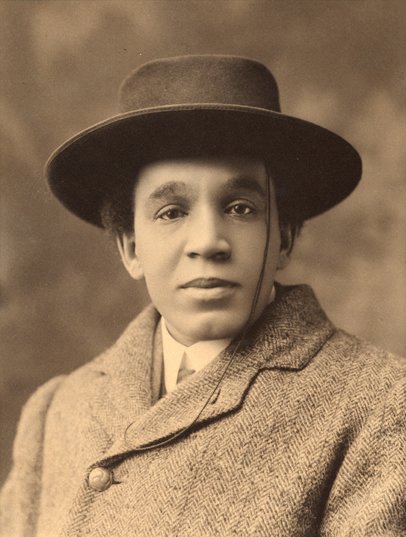

On Sunday, April 10 2022 at 2 pm in the Schermerhorn Center, the Nashville Symphony continued its “Classical Series” with four works, two familiar and two relatively unknown in the US. Each half opened with a composition by Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875–1912). After starting violin studies with his father, a descendant of American slaves relocated by the British to Sierra Leone, the prodigy Coleridge-Taylor entered the Royal College of Music in London at the age of fifteen. Later, he was mentored by English musical icon, Edward Elgar.

Coleridge-Taylor not only celebrated his own musical heritage, but he was open to other cultures, including tales of Native Americans. With guest Thomas Wilkins, principal conductor of the Hollywood Bowl Orchestra, the Symphony played three movements from the Hiawatha Suite, op 82, based on excerpts from the composer’s Song of Hiawatha cantata cycle, itself based on Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s epic poem. The orchestra immediately set a lush orchestral timbre of muted strings and a beautifully played solo by Erik Gratton, principal flutist, floating ethereally above the pastoral first movement where Hiawatha woos Minnehaha in the forest.

The delightful “Marriage Feast” had just the right degree of playful charm before the majestic ending with a sizable string section blending well with the brasses. The last movement of this set, “Conjurer’s Dance,” began with an anticipatory tension similar to the final “Witches Dance” of Berlioz’ Symphonie Fantastique, its sections of demonic sprightliness, beautifully executed.

Coleridge-Taylor’s Ballade, op 33, marked enérgico, launching the second half, effectively characterizing a variety of tempo and affect changes from genteel to passionate, delicate to dramatic. Although the sound remained luscious or light as appropriate, the many noted tempo changes seemed a bit too restrained, too cautious—the appassionata lacking passion; the con fuoco lacking fire. But overall these well-received performances lit a fire under the audience, convincing them that this was a composer to be reckoned with. It’s no surprise, that having heard his works during three US tours, President Theodore Roosevelt invited Coleridge-Taylor to the White House to honor his service to music. Although little-known today, Coleridge-Taylor’s Hiawatha often vies with Handel’s Messiah for popularity among choral groups in the UK. Serendipitously, Messiah is the next concert in NSO’s classical series, April 14–16, 2022. Tickets available here.

Ending the first half was Mendelssohn’s famed violin concerto, featuring Adele Anthony. Like Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker, Mendelssohn’s concerto is a perennial favorite that continues to draw audiences over a century after its premiere. Fan favorites like these bring in ticket fees that help sustain organizations like the Nashville Symphony, especially as arts organizations rebuild from the ravages of Covid cancellations.

However, for a piece this renowned, the soloist and/or the conductor need to have a vision of offering either a perfection of performance traditions, or a new take on the work’s subtleties. Of course, this concerto is written so well that if the soloist and orchestra merely conquer the many challenges Mendelssohn wrote—notes, tempos, dynamics—the piece will excite audiences as it did in this performance. But should that be enough?

In each movement, Mendelssohn included one of three stylistic tropes common in this part of the Romantic era: Sturm und Drang, Emfindsamer, and brilliante. The first movement, marked “molto appassionato” should be Sturm und Drang, full of sound and fury, but this performance would be deemed “B-flat” in jazz, fully competent, but not much more.

This uninspired quality continued through the second movement which should have represented Empfindsamkeit, the sensitive, emotional style found in literary works like those of the Brontës where the chains of a rigid society bind passionate hearts. This part, the best opportunity for Anthony to really “sing” was, metaphorically, out of tune, with little sense of line or nuance.

The last movement showed her real strength. It is the flashiest of the three, with lots of notes, tons of speed, tricky passages out the wazoo— a major part of the concerto’s value as a crowd pleaser. Anthony handled all this with ease, seeming to enjoy herself for the first time in the concerto. It was disappointing that the emotional depth needed for the first two movements didn’t match the joyous bravura of the finale.

The program’s final work, Claude Debussy’s La mer was a marvel of a performance. La mer, his “sonic portrait of the sea,” is a masterwork of Impressionism in which the composer sought to produce “the mysterious correspondences which link Nature with Imagination.”

Reports of Debussy conducting this work describe him as “stiff” with an almost obsessive attention to detail. Wilkins used efficient, almost utilitarian movements, with no large dramatic gestures like Leonard Bernstein in his heyday, but the proof is in the results. Like Poseidon, Wilkins was able to command the waves of La mer. As in the Coleridge-Taylor suite, the opening timbral seascape of “From dawn to noon on the sea” was exquisite with Debussy’s occasional use of Japanese modes shining with just the right amount of delicacy. Occasionally, mid-movement, the tonal quality and blend lost some purity and direction but the entry of the French horns and trombones reshaped the waves before the audience broke the mood with spattered applause between movements.

Some of Debussy’s most challenging orchestration is found in “Play of the Waves.” The magical timbre added by the glockenspiel and, toward the end of the movement, the unlikely but perfect synthesis of piccolo, harp, and basses was handled masterfully. During the bows, alongside soloists among the winds and strings, the conductor appropriately acknowledged the entire cello and percussion sections, the firm canvas for this lyrical portrait.

But before that, came the “Dialogue of the wind and the sea.” Once more the momentum briefly flagged, but once again, the horn entries guided the stormy waters toward a dynamic finish. I’ve always thought that a compelling performance of even the most emotionally or intellectually challenging work can convince the audience of the composer’s greatness. That was the case here. Debussy is not a facile listening experience, but the Symphony convinced a willing audience of La mer‘s greatness, responding with vigorous applause.