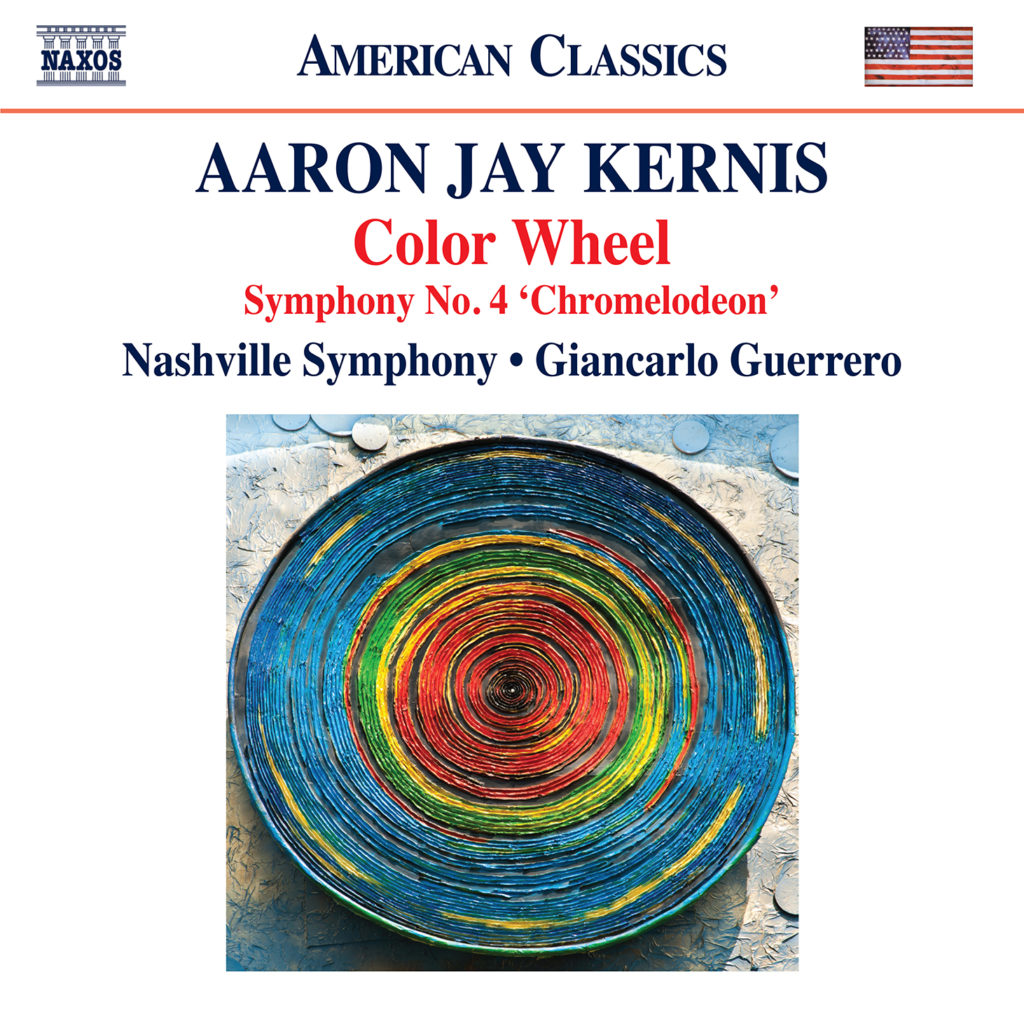

A New Recording from the Nashville Symphony:

Aaron Jay Kernis’ Color Wheel and 4th Symphony, “Chromelodeon”

The Nashville Symphony just released it’s newest recording on Naxos’s American Classics series. Featuring two works by Pulitzer, Grammy and Grawemeyer Award winning composer Aaron Jay Kernis, Color Wheel (2001) and Symphony No. 4 ‘Chromelodeon (2018), this recording will complement well the Symphony’s already extensive collection of contemporary music recordings (listed here: https://www.nashvillesymphony.org/media/recordings/). Kernis, who wrote the wonderful liner notes (unfortunately printed in a miniscule font) approves of the pairing, describing the two pieces as “…like related family members – one brash and exuberant, the other more serious and pensive in intent, though no less bold in manner.” One imagines this to be Kernis lending voice to his version of Schumann’s personas “Eusebius” and “Florestan,” allowing them to be heard at the Schermerhorn. However, it isn’t really one of Schumann’s several personalities that I hear in Kernis’ work, instead it is an expression in orchestral color resembling Strauss, bound up with an American sound that features terrifying dramatic crescendos contrasted with intimate, poignant, or at times downright creepy quiet moments, all unified through the subtle employment of thematic variation and rich chromaticism.

The Nashville Symphony just released it’s newest recording on Naxos’s American Classics series. Featuring two works by Pulitzer, Grammy and Grawemeyer Award winning composer Aaron Jay Kernis, Color Wheel (2001) and Symphony No. 4 ‘Chromelodeon (2018), this recording will complement well the Symphony’s already extensive collection of contemporary music recordings (listed here: https://www.nashvillesymphony.org/media/recordings/). Kernis, who wrote the wonderful liner notes (unfortunately printed in a miniscule font) approves of the pairing, describing the two pieces as “…like related family members – one brash and exuberant, the other more serious and pensive in intent, though no less bold in manner.” One imagines this to be Kernis lending voice to his version of Schumann’s personas “Eusebius” and “Florestan,” allowing them to be heard at the Schermerhorn. However, it isn’t really one of Schumann’s several personalities that I hear in Kernis’ work, instead it is an expression in orchestral color resembling Strauss, bound up with an American sound that features terrifying dramatic crescendos contrasted with intimate, poignant, or at times downright creepy quiet moments, all unified through the subtle employment of thematic variation and rich chromaticism.

Color Wheel was composed for the opening of the Verizon Hall at the Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts in Philadelphia where it was premiered by Philadelphia Orchestra (one of the original “Big Five” orchestras) under the baton of the great Wolfgang Sawallisch.

A miniature concerto for orchestra, written for the Philadelphia Orchestra no less, is no small challenge, but Maestro Giancarlo Guerrero and the Nashville Symphony prove themselves up to the task. Ever the master of articulating the subtle reprise, Guerrero led the Nashville Symphony from the terrifying opening chords through the piece’s kind of circular form in which these chords (and motives derived there-from) return over and over again. The form is both symphonic and blustering, moving through a blistering fast scherzo that ambushes the opening section, only to lead to an interruptive slow section, before returning again with the opening idea as an expressive dénouement in orchestral color; It is an inspired movement.

Kernis’ says that in 2018 a Symphony “can seem anachronistic” but he justifies the genre through its Mahlerian ability to “contain the entire world,” and push “…past boundaries of what I’ve explored in my work up to that point.” With his Fourth Symphony, entitled Chromelodeon , he has created a world that is richly chromatic, marked by unease, contemplative intensity and, in the first movement particularly, obsessive rumination. Subtitled “Out of the Silence,” the first movement reveals a composer much more in tune with his process, achieving in a quiet tune for viola the same expressive intensity that would have demanded bombast and bluster a decade earlier. It’s not pretty, but that isn’t Kernis’s goal, it is intense.

The Symphony’s second movement, entitled “Thorn Rose I Weep Freedom (after Handel)” draws its primary melody from a vague influence of Handel, and juxtaposes chromaticism with consonance which is, at times, even presented simultaneously through separate registers, dynamics or timbre. The consonance is deconstructed by the chromaticism in a striking process. The initial consonances sound in an interesting and almost Coplandesque pan-diatonicism but after being subjugated to waves of the “hectoring” chromatic, results in an ethereal, Ives’ inspired (vox angelical) sub-conscious attenuation that, as Kernis describes it, appears “broken and distorted.” This last is played with remarkable clarity by Nashville’s strings, and Guerrero’s handling of this movement’s precarious balance is nuanced and deft.

…there yet remains remarkable power in absolute expression.

The third and final movement continues the juxtaposition, but introduces a rhythmic component placing a slow horn chorale and fanfare against busy and disjunct melodies. This, the shortest movement, turns the previous narrative on its head and ends with a final, climactic perfection—it is a heroic tale told in absolute musical terms, despite all of the movement titles. As Kernis describes it “This new symphony is created out of musical elements, not images or stories…” Perhaps it is anachronistic, but there yet remains remarkable power in absolute expression.

Contemporary music is often regaled for its accessibility, Kernis’ work stands against that. It is interesting and complicated music that draws on the work of great minds that precede it and greatly rewards repeated hearings. This recording will find its due place in the pantheon of American Classics, as the series label suggests. The first of three due out from Naxos and Nashville this summer, it looks to be a very nice season—even if we are all stuck at home.

As a final note: Particularly with the Color Wheel, but also with the Chromelodia Symphony, hearing this recording flooded me with a sense of nostalgia for the Schermerhorn with its light touch of reverb and responsiveness to forte blasts. Kernis especially wrote his Color Wheel to bring out the sound of the space and our great Maestro Guerrero succeeds in making the Schermerhorn ring. I miss the Nashville Symphony and while I understand the necessity of the current suspension, I’m taken aback at its length. Other orchestras have found a way to continue, some online, whether live or recorded (Philadelphia, Chicago, London) or live performances to socially distanced audiences (Vienna, Berlin). Even Nashville Opera is surveying its options, but very few have simply cancelled the entire season. It feels like we have witnessed the end of an era.