Spano and Trpčeski with the Nashville Symphony

On the first weekend in May the Nashville Symphony gave a concert featuring Michael Gandolfi’s The Garden of the Senses Suites, Jean Sibelius’s Symphony No. 5 in E-Flat Major, Op. 82 and Sergei Rachmaninoff’s epic Concerto No. 3 in D Minor for Piano and Orchestra with Simon Trpčeski on piano and Robert Spano at the podium. The evening was mixed, but ended wonderfully.

The concert opened with Gandolfi’s Suite. Written on a commission by guest conductor Robert Spano, the piece is one of a series titled the Garden of Cosmic Speculation and was inspired by Charles Alexander Jencks’s Garden of Cosmic Speculation, and actual garden outside Dumfries, Scotland which, “celebrates nature and his [Jencks’s] own fascination with advances in cosmology, genetics, chaos theory, fractals and other areas of contemporary science.” One of thirteen movements in the composition, the suite is organized along the lines of one of Johann Sebastian Bach’s suites with each movement corresponding to a dance movement. Further, each movement is meant to also correspond in a synesthetic gesture to one of the other senses: Allemande (Audition), Courante (olfaction), Sarabande (gustation), Passepied (palpation), Gigue (vision), and Chorale (the sixth sense: intuition).

Obviously, there is an awful lot going on here to digest in one hearing, but ignoring all of this and just paying attention to Spano’s realization of Gandoli’s genius for style and instrumentation was quite rewarding. The waves of chromaticism in the dignified first movement, and the sparkling pizzicato strings in the Passepied were remarkable. My favorite was the last movement, a setting of Bach’s chorale “O wie selig seid ihr doch, ihr Frommen” set in a rhythmic and registrational self-reflexive commentary in which, as Gandolfi described it, the “…music anticipates or in

tuits itself.” Spano’s interpretation showed his knowledge of the piece and his talent for interpreting contemporary American music.

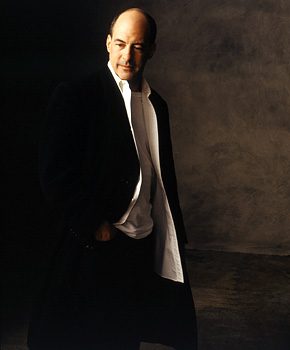

Maestro Spano is a world-class conductor and has done amazing things with the Atlanta Symphony in his two-decade tenure there. After winning six Grammys and surviving a dreadful lockout in 2014, he has certainly earned the esteem he

has garnered and when he begins his new position in Fort Worth in 2021 there is a lot of appropriate optimism. However, his approach with the baton is remarkably different from our own Maestro Guerrero, a difference that might be exaggerated in comparing the reserve of Richard Strauss to the vigor of Georg Solti, and this difference came through in the Sibelius.

Jean Sibelius began work on his Fifth Symphony in 1915 and it underwent a number of revisions before achieving its final form in 1919. It features a highly developed organicism that rests on the slow emergence and dénouement of the famous “swan theme” in the primary climax of final movement, presented by the horns. The piece as often been described as “regressive” from a formal and harmonic point of view, but this accessibility can conceal a remarkably intuitive formal organization. On Friday there were marvelous moments, in the Andante in particular where Nashville’s woodwinds deserve special mention, but the grand sweep of Sibelius’s piece felt off balance, the famous final chords more perfunctory than transcendent.

The epic work depicted in the movie Shine, a docudrama of child prodigy David Helfgott’s troubled career, Rachmaninoff’s Third Concerto is often described as the most difficult piece in the concert repertoire of the piano. However, after intermission when Simon Trpčeski breezily strolled on stage to present it, his confidence was infectious. Beginning the

famous first theme with a marvelous singing tone and constantly attentive to Spano and the orchestra, by the arrival of the second theme, Trpčeski seemed to bring orchestra, conductor and himself into alignment for an extraordinary and explosive performance.

He took to the powerful cadenza, playing the earlier and longer version, with a certain joy, stretching his legs out beneath the piano as the entire stage seemed to move as one. The intermezzo and final movement were equally great to the first, with the maze of themes in Rachmaninoff’s final movement articulated as though it was a walk through an (astoundingly) beautiful park. At the final cadence the audience leapt to its feet and would not calm until treated to an encore—which Trpčeski obliged. (I hear he did on Saturday too). The Classical Series continues on May 17th with Thibaudet Plays Turangalîla, a rarely heard masterpiece by Olivier Messiaen featuring the otherworldly, electronic ondes-Martenot.