Nature and the Nashville Symphony

On the weekend of March 8 and 9 the Nashville Symphony offered a pastoral program featuring Tobias Picker’s The Encantadas narrated by Picker himself and Gustav Mahler’s epic masterpiece Das Lied von der Erde (The Song of the Earth). Here on the very precipice of spring, it was a beautiful concert for a rainy night in Music City.

Picker, who has been cited by the Wall Street Journal as “our finest composer for the lyric stage” has a talent for dramatic depiction. The last time the Nashville Symphony performed one of Picker’s works it was his Opera without Words, which featured singing but without text, here it is the opposite, a melodrama made up of narrated text and accompanied by the orchestra. Picker drew on Herman Melville’s text for the Encantadas, which Melville wrote in 1854 while he researched for his Moby Dick in the Galápagos Islands onboard a whaling ship. Adopting Melville’s use of alliteration, Picker named his six-movement work Dream, Desolation, Delusion, Diversity, Din and Dawn respectively.

Picker’s score is dark and pensive, strikingly (neo-)romantic and beautiful but is always guided by the text. The striking entrance of the horns in the first movement, handled so well by Maestro Guerrero’s deft measure of balance and dynamic, wonderfully brought the “evilly enchanted ground” of Melville’s imagination to life. Indeed, the first movement served as a frame, describing the whole piece as a kind of memory. What followed was a string of marvelous depictions of a day in the Galápagos, from the “lashing rocks” to the “waltzing pelicans” pursuing the day, through the night and back into the dawn, with rarely a break between movements. In all, as a composition, the piece is a narration accompanied by orchestra and Guerrero never allowed the music to overwhelm Picker’s narration – a wise decision and a noted weakness of the existing recording. I am quite excited to purchase the recording being made of this performance.

One of the primary differences between Picker’s nature and Mahler’s is that Mahler’s is born of the Romantic ideal of man’s presence and part in nature itself. Whereas Picker’s narrator is an active observer of nature, Mahler’s narrator is a participant. The poet’s inner life is connected and paralleled with that of the external:

I weep often in my loneliness.

Autumn in my heart lingers too long.

Sun of love, will you no longer shine

Gently to dry up my bitter tears?

It is this perspective that provides Mahler’s piece its depth, breadth and gravitas, making this sixty-minute work seem much more than merely twice as long as Picker’s.

For the vocal parts, Nashville brought in mezzo soprano Michelle DeYoung whom we heard sing Verdi’s Requiem last season and tenor Paul Groves (replacing Anthony Dean Griffey just this past Wednesday) in the male part. Both performed quite well. Grove’s warm, clarion instrument was pushed to its ends in the first movement’s famous phrase “Dunkel ist das Leben, ist der Tod,” (Dark is life, is death) which appears a half step higher over and over again. This stress, imagined and intended my Mahler who was just coming to terms with his own mortality at the time, provided a remarkable opening movement.

Groves’ performance in the other two movements for his part, “3. Von der Jugend” and “5. Der Trunkene im Frühling” (often described as the work’s Scherzi in Mahler’s symphonic form) was equally marvelous.

Concertmaster Jun Iwasaki and Principle flutist Érik Gratton handled their solos admirably in the fifth movement drawing Mahler’s pastoral scene with a deft beauty.

However, if the male role is graced with the opening movement of the form, the female role will always win out because it is her part that brings the world that Mahler has created to an end. Indeed Mahler has built an expressive crescendo into her part. After a “somewhat dragging” (Etwas schleppend) and “weary” (Ermudet) second movement (2. Der Einsame im Herbstand” The Lonely Man in Autumn”), and the more exotic fourth (“4. Von der Schonheit” on Beauty), the finale, “6. Der Abschied” (The Farewell) brings the whole of the symphony to a formal and programmatic conclusion.

DeYoung performed with admirable precision, and great patience. In the second and fourth movements she maintained a certain amount of emotional restraint that allowed for a crescendo of feeling in the final movement. As the texture of the movement finally receded into the pedal point in the strings against Gratton’s lonely flute, DeYoung intoned the closing mantra “ewig” (forever) and it seemed as if the air had been simply pulled from the room. When the Maestro lowered his shoulders, I counted a good 90 seconds before the first wave of their earned standing ovation.

The Classical Series at the Nashville Symphony continues on the 21st with “Spanish Nights” featuring Peruvian conductor Miguel Harth-Bedoya

- About the Author

- Latest Posts

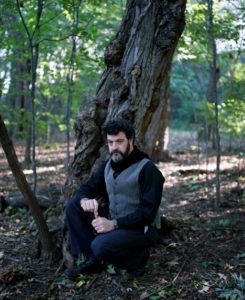

Joseph E. Morgan is a father of two, husband, teacher and recovering guitarist in Middle Tennessee.