The Nashville Symphony in Fine Form with Haydn, Schubert and Martin

The program presented by the Nashville Symphony on October 12th, may not upon initial consideration generate an obvious theme for an evening of orchestral music. Haydn’s Symphony 104 “London,” Schubert’s Symphony No. 8 D. 759 in B minor “Unfinished,” and the Concerto for Seven Wind Instruments and Timpani by 20th century composer Frank Martin don’t share any obvious connections. But, a consideration of the compositional devices and organizational elements presented in these works paired with the nuanced interpretation of the Nashville Symphony under the direction of Maestro Guerrero, afforded listeners the opportunity to enjoy an evening of superb musicianship through the vehicle of a thoughtfully crafted program.

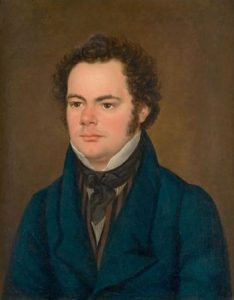

The evening began with Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony, a piece that in only two movements takes listeners through a carefully orchestrated dramatic juxtaposition of light and dark with a heavy dose of the contrasts and harmonic manipulation present in much of his lieder. Schubert composed these two movements in 1822 at the age of twenty-five, and though he finished many other works including a ninth symphony before his death in 1828, the eighth symphony remained “unfinished.” Some scholars have suggested that after becoming terminally ill shortly after completing these movements, Schubert had difficulty working on a piece that he may have associated with his own sense of mortality. But, he had little trouble musically confronting the inevitability of his own death as evidenced by his string quartet no. 14 (1824) which recycles melodic material from his “Death and the Maiden” (1817), a lied that addresses the eventual acceptance of death via harmonic transformation. Why then did Schubert not “complete” the eighth symphony? Perhaps it is because the strength and narrative flow of the two finished movements form a complete musical statement that will not easily permit continuation. Though with only two movements it doesn’t follow conventional symphonic form, Schubert’s “unfinished” symphony is a crowd pleaser and is routinely performed as a stand-alone work. Had he not died in 1828, the later popular romantic vehicle of the symphonic poem would have held untold potential for Schubert.

The “unfinished” symphony allows listeners to experience the harmonic, melodic, and structural developments Schubert had long exhibited in his lieder within a larger symphonic context. In the first movement, the stark contrasts of the harsh minor themes conjured forth by the dark opening statement and the soft spoken light-hearted thematic gestures that follow, require a rapid shift in character, and the ensemble was equal to the task. The dramatic pauses used to punctuate some of these changes, often stopping lyrical content in what seems like mid-sentence, were masterfully handled by the orchestra. One could almost see the audience leaning forward in anticipation of the downbeat we all knew would arrive, but were happy to delay in order to share together the silence of perfect expectation. Schubert’s harmonic shape in the second movement is a broad inversion of the first, with an initial major theme followed by a minor theme that eventually snakes its way harmonically back to the original key for an ending that may be characterized as peaceful, but not subdued. It may not exist in a standard four movement structure, but Schubert’s “unfinished” symphony has the strength to stand alone.

Schubert’s emotionally charged offering was followed the Nashville Symphony’s premiere performance of Swiss composer Frank Martin’s Concerto for Seven Wind Instruments and Timpani (1949) featuring Érik Gratton (flute), Erik Behr (oboe), James Zimmerman (clarinet), Julia Harguindey (bassoon), Leslie Norton (horn) Jeffrey Bailey (trumpet), Paul Jenkins (trombone), and Joshua Hickman (timpani). Treating each of the orchestra’s standard wind instruments (with the exception of the tuba) and the most commonly used percussion instrument as soloists, at once calls to mind a possible interplay of the expectations of the traditional coloristic roles they occupy and a concerto grosso format allowing individual voices and subsets to shine. Within a modern aesthetic, the sometimes blocky baroque concerto grosso can limit the interaction between the soloists and the ripieno group – outlining a clear definition of what “should” be important to the listener. But, Martin’s approach draws on elements of tradition while treating each solo instrument as its own tone color, allowing the character of the instrument and the player to dictate the development of the work. Through his choice of soloists and his construction featuring color and characteristic as structural components, Martin has married the concepts of the traditional function of symphonic winds with the soloistic nature of the concerto grosso, all within a traditional three movement concerto structure.

Martin’s allusions to baroque tradition are perhaps most easily seen in the second movement through his use of a clearly articulated and unchanging rhythmic foundation and repetitive string entrances between the soloists’ lines. The jagged lines and technical fireworks of the first movement give way to a lyrical virtuosity in the slow second movement, allowing the soloists to sing. Martin’s rhythmically static accompaniment forces listeners to focus on the longer solo lines, and though the rhythmic figures are steady, Martin subtly alters his accompaniment’s range and timbre to mirror the characteristics of the solo instruments. This is most clearly heard in the initial high bassoon melody hauntingly played by Julia Harguindey, and its darker repetition beautifully expressed by Paul Jenkins on the trombone. Each statement features an individualized setting for these two colors. The movement concludes with a sublime tapered sigh at the end of the trombone solo, inviting the audience to slowly exhale along with the orchestra.

The virtuosity displayed by the soloists was staggering. Gratton, Behr, Zimmerman, and Harguindey effortlessly navigated thorny and angular lines, while the fanfare gestures played by Norton, Bailey, and Jenkins were clean, crisp, and brilliant. Frank Martin even carved out a space for a timpani solo, allowing Joshua Hickman to weave a dynamically varied melodic statement that instead of acting as a predictable “drum break”, instigates an eventual role reversal allowing the soloists to provide a syncopated accompaniment against the soaring string section. The work ends much as it begins with the solo contingent leading an impressively dizzying charge toward a climactic punctuation.

The evening concluded with Haydn’s last symphony, “London” no. 104, (1795). The “Father of the Symphony” needs no introduction, but it bears mentioning that his symphonic output provided the model that many composers followed. Specifically in his later works, Haydn’s use of the process of musical form to express the elegance and possibilities of a musical idea’s transformation rather than a treatment of form as a mold to simply fill, resulted in some of his most popular

works. It is fitting then that maestro Guerrero elected to end a concert of non-traditional forms with a defining work from a composer who both served to establish and expand the process of form within a symphonic setting.

Though the audience and performers were all comfortable with Haydn’s familiar work, the orchestra’s interpretation and enthusiasm kept the piece fresh. Maestro Guerrero’s bright tempo in the last movement allowed the finale to act as a true endcap for the evening. The character of the movement is folk-like after all, and the brisk pace permitted the orchestra to shout, sing, and whisper the iconic melody with rollicking glee.

Perhaps a concert organized around the concept of musical form is a stretch for some listeners, and by all means the superb musicianship alone was worth braving the downtown Nashville traffic. But, for the nerdy music fanboys among us who smile and push our glasses further up the slopes of our noses at the bare mention of Schubert and chromatic mediants, this kind of programming could only have been an artistic and intentional choice.

- About the Author

- Latest Posts

Brad Baumgardner is an unapologetic music nerd who listens to Rossini, Reich, and Radiohead with equal joy. As a composer and new music clarinetist, he has a particular soft spot for thoughtfully crafted and well orchestrated contemporary music. He lives in Nashville with his wife and children, none of whom own or wear cowboy boots.